Hero Horses in the Fight Against Disease

by Charles Richter and John Emrich

October 2021

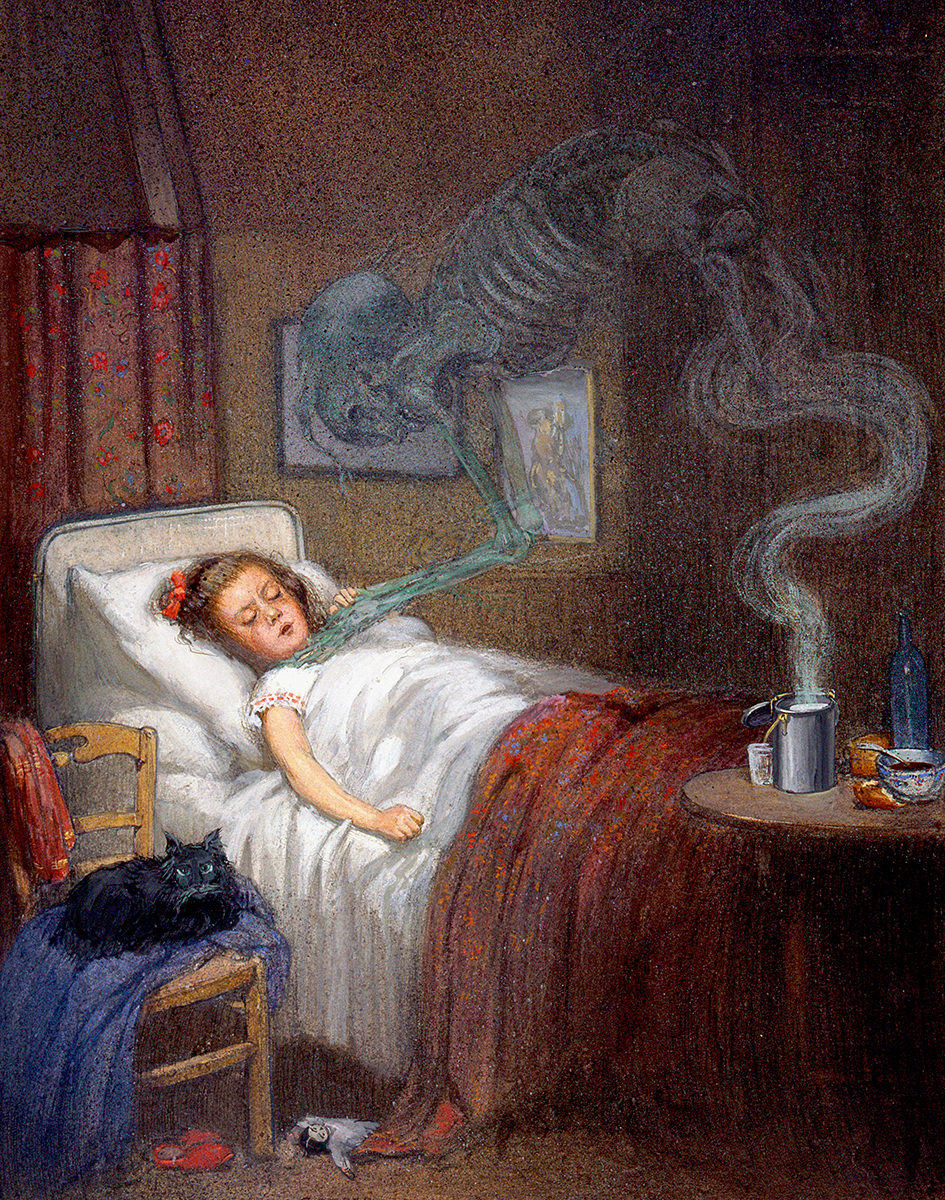

Painting depicting diphtheria, c. 1912

Painting depicting diphtheria, c. 1912

Wellcome CollectionIn the December 10, 1894, edition of the New York Herald, a headline announced: “ANTI-TOXINE FOR THE POOR.” After three years of rising death tolls among the city’s children due to diphtheria, the newspaper was making an appeal to its readers for donations to support a new and exciting medical treatment: antitoxin serum.

The publishers of the Herald pledged $1,000 to begin the fund drive, and the money began coming in rapidly, doubling the initial pledge in only four days. In daily updates, readers were informed about the science behind the new treatment and the scientists at the Pasteur Institute and the New York City Department of Health who created it. Readers also learned about the crucial role of horses in serum production, beginning a long tradition of recognizing hero horses in the biologics industry.

Diphtheria

Death caused by diphtheria was not uncommon in late 19th century New York City. In the century’s next-to-last decade, two spasms of epidemic diphtheria had ripped through the city, claiming 4,894 and 4,509 citizens in 1881 and 1887 respectively.

Diphtheria is caused by the Corynebacterium diphtheriae bacteria, identified in 1883 by Edwin Klebs, and typically transmitted human to human via respiratory droplets. The bacteria secrete a powerful toxin that damages body tissue, predominantly in the mucosal membranes. Early symptoms are indistiguishable from other infections: sore throat, low-grade fever, malaise, and loss of appetite. But as the disease progresses, the most identifiable symptom of diphtheria appears—first a bluish-white membrane on the tonsils, soon followed by a thick gray-green substance spread over the tonsils, larynx, and nasal tissue. Known as a pseudomembrane, it adheres to tissue and is caused by the release of toxins that increase waste products and proteins.

For patients who do not experience early recovery, the disease progresses to a more critical stage. Toxins can travel to and damage internal organs, including the heart, kidney, and liver, causing neuritis, and obstructing the airway (giving diphtheria its nickname of “the strangling angel of children”). If enough toxin is absorbed, the patient can lapse into a coma. Death can occur in six to ten days.

Diphtheria was a major cause of illness and death in children, and in 1890 “about one half” of the deaths caused by diphtheria and croup occurred in children under the age of five. In the 1890 census, diphtheria was the sixth highest cause of death in the United States for the previous year, behind only consumption (tuberculosis), pneumonia, diarrheal diseases, heart disease, and stillbirth. If deaths caused from diphtheria (27,815) and croup (13,862) are combined (97.75 per 100,000 of population), diphtheria becomes the number four known cause of death. (In the late 19th century “the majority of cases of death attributed to croup are due to diphtheria of the upper air passages.”)

For comparison, the corresponding death rate in 1890 from diphtheria and croup was, in England and Wales, 28.8; in Ireland, 21.3; in Scotland, 44.0; in Belgium, 56.5; in Prussia, 145.4; in Austria, 120.0; and in Italy, 50.0.

Antitoxin

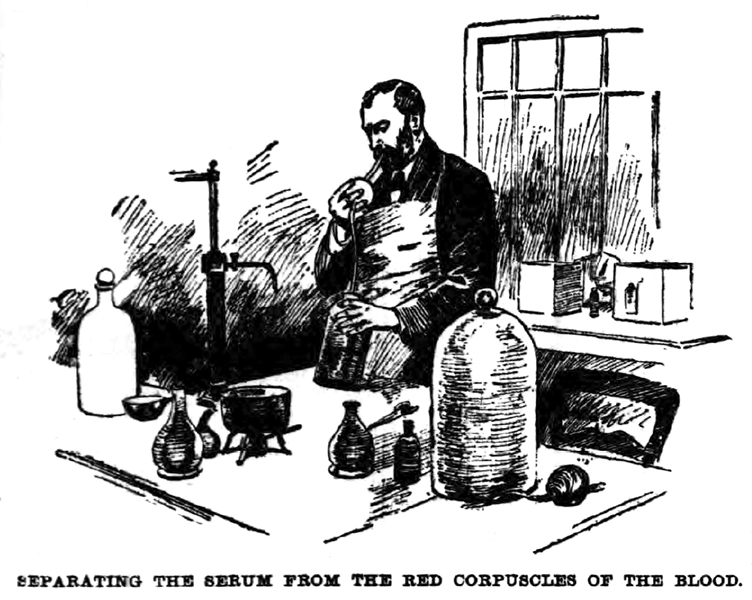

Bleeding a Horse for Serum, 1894

Bleeding a Horse for Serum, 1894

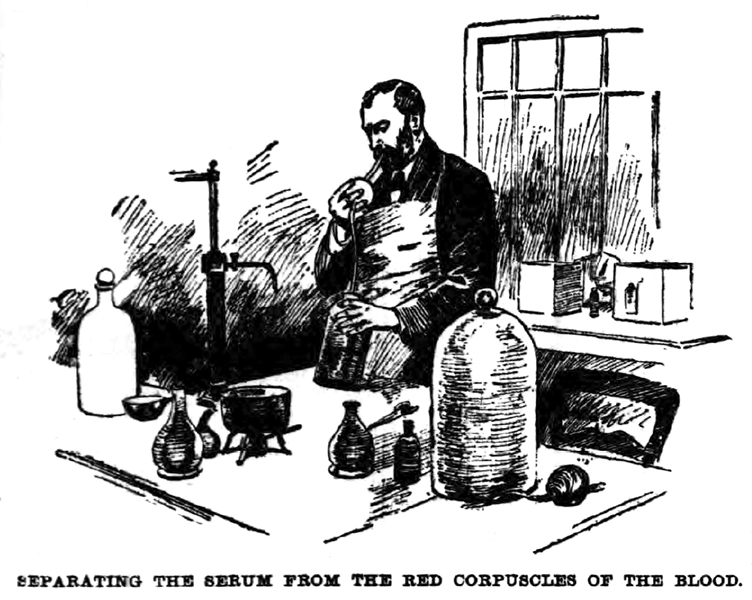

New York HeraldThe first successful treatment for diphtheria was the administration of an antitoxin. An antitoxin serum was produced by inoculating horses with small amounts of the diphtheria toxin—enough to immunize without harming the animals. The horses would then be bled periodically. The technician would cool the blood and separate the antitoxin-rich serum from the clotted red blood cells using mouth or mechanical suction. Emil von Behring had discovered this process in 1890, and diphtheria antitoxin produced via a methodology created by Émile Roux at the Pasteur Institute was being used with great success in Europe. The small amounts of antitoxin brought to the United States by individual scientists saved a few lives but could not put a dent in the growing diphtheria problem here.

Diphtheria Antitoxin in New York

At the New York City Department of Health, pathologist Hermann R. Biggs and laboratory director William H. Park (AAI 1916, AAI president 1918–1919) were following the news from Europe about the successes of antitoxin treatment, and along with several other leading physicians and scientists, appealed to the Herald to start the fund drive. Their backing prompted many New Yorkers, rich and poor, to make contributions. Nathan Strauss, owner of Macy’s, gave $500, while others gave a dollar or took up small collections at their offices. World-famous opera singers and actors made significant donations as well.

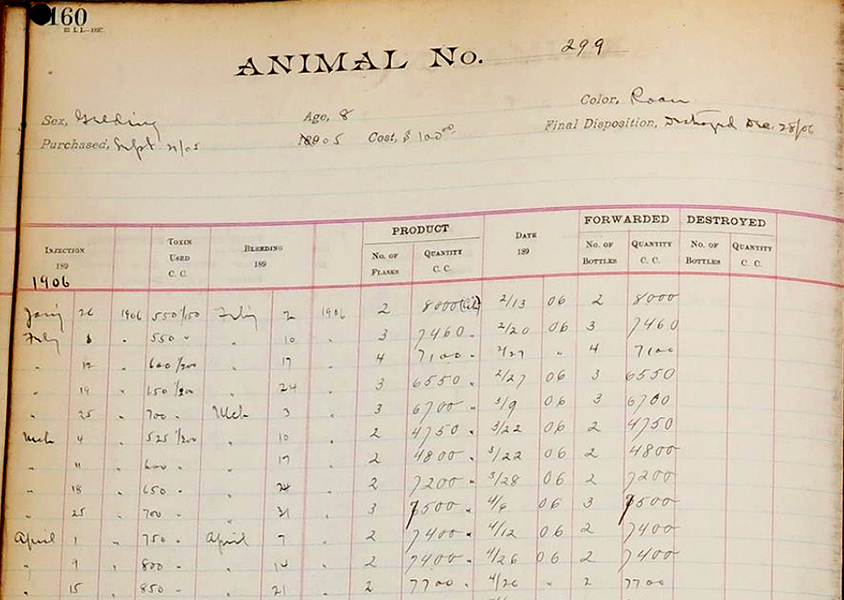

Serum Horse Record Book, NYC, 1909

Serum Horse Record Book, NYC, 1909

National Museum of American HistoryJust five days after the initial announcement, Biggs, Park, and T. Mitchell Prudden began inoculation of the first horses at the Department of Health, and quickly expanded the antitoxin production facility into new stables that they called the “Herald Annex.” Park and his new colleague Anna Wessels Williams (AAI 1918) were able to improve upon Roux’s method for making diphtheria toxin with which to inoculate the horses. Williams had compared several different strains and found one that produced as much toxin in vitro in one week as Roux’s had in a month.

By Christmas 1894, 30 horses were busy producing antitoxin. On the first day of the new year, Park administered the first doses of serum treatment to two children at the Willard Parker Hospital, with “favorable reactions,” even though one of the children had not been expected to survive.

Park immediately began a six-week trial of the antitoxin and demonstrated that when given to patients early in the disease’s course, it was effective in stopping further progression. This success led to the widespread adoption of serum production by municipal health departments in many other American cities.

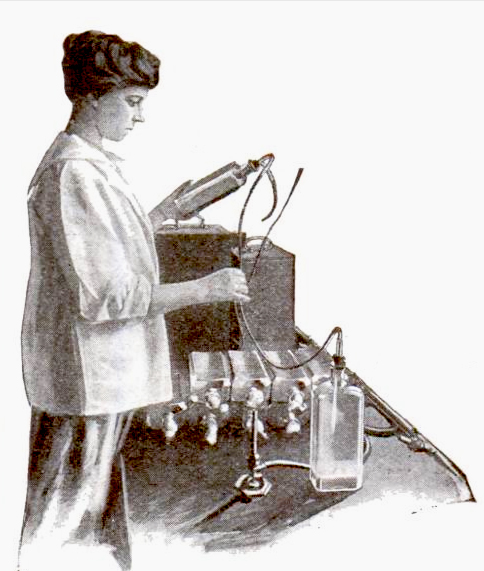

Preparing the Serum

Preparing the Serum

Popular Science A year after the initial fundraising appeal went out, the Department of Health passed a resolution acknowledging the contributions of the Herald Anti-Toxine Fund, which eventually totaled $7,496.82, to help begin the production of antitoxin and make it available to the poor of the city.

The St. Louis Antitoxin Tragedy

Following New York’s success, St. Louis, MO, set up a municipal diphtheria antitoxin production facility, but lack of careful oversight led to tragedy. A retired milk-wagon horse named Jim provided the serum for the city’s antitoxin, which initially proved effective. But at the end of October 1901, May and Bessie Baker, two sisters aged four and six, died after being given diphtheria antitoxin. Their two-year-old brother died a few days later, also after receiving antitoxin treatment. Diphtheria did not kill them, though; they all died of tetanus.

The children’s doctor, R. C. Harris, had been called to treat Bessie, who was suffering a severe case of diphtheria. He gave the antitoxin to all three children as a precaution. Harris reported the deaths to the St. Louis Health Department and discovered that at least two other children who had received antitoxin from the city supply had also been killed by otherwise unexplained tetanus.

Inquest

Amand Ravold, 1901

Amand Ravold, 1901

St. Louis Republic Officials at the Health Department began an investigation and within days announced that the serum had come from a horse named Jim. The old horse had been inoculated on September 22 and bled on September 30. His handlers recognized signs of tetanus the very next day and euthanized Jim on October 2. According to the Health Department’s records, none of the serum from the September 30 blood draw had been distributed or used. Jim had also provided serum on August 24, but at that time he had been in perfect health. All of the serum had been prepared under the supervision of the city bacteriologist, Amand Ravold.

By November 5, 11 St. Louis children had succumbed to a painful death from tetanus, and a legal inquest had begun taking testimony. A veterinarian testified that Jim should have been immunized against tetanus, a practice that was “in vogue” at east coast antitoxin facilities. Robert Funkhouser, the city coroner, determined that serum from the September 30 blood draw had in fact been used to produce serum, and furthermore that some of that serum had been mislabeled as part of the August 24 batch. He confirmed through testing that this serum was tainted with tetanus toxin.

Testimony

On November 30, assistant bacteriologist Martin Schmidt finally broke his silence, testifying that Ravold had not tested the serum on guinea pigs before its release. He had kept quiet about this because of his personal friendship with Ravold. Schmidt also implicated Henry Taylor, an African American janitor in the Department of Health, who had been given unlabeled flasks of serum from both blood draws and directed to bring them to Schmidt, with no way to distinguish them but reliance on his own memory. Taylor, of course, had no idea that any of the serum was tainted.

The final outcome of the inquest was the dismissal of both Ravold and Taylor. Officially, responsibility for the deaths of 13 children was judged to be Ravold’s. Taylor bore no blame for the tragedy, but the inquest commission decided he had obstructed the investigation with contradictory statements during his testimony. No criminal proceedings were recommended.

Federal Regulation of Biologics

Separating the serum, 1894

Separating the serum, 1894

New York HeraldThe tragedy in St. Louis could have been a disaster for the future use of antitoxin, but the inquest clearly showed that the serum itself was not the culprit. Diphtheria remained a dreadful threat to children, and antitoxin was so far the only reliable treatment or preventative. To preserve both safety and public confidence in antitoxins and vaccines, Congress passed the Biological Products Act of 1902, also known as the “Virus-Toxin Law.” The Act required federal licensing of facilities producing biologicals for interstate shipment, and established safety reviews and approvals before products could be released. Authority to enforce the Act was given to the Hygienic Laboratory of the Marine Hospital Service, which evolved into the National Institutes of Health in 1930.

Horses as Heroes

With new national standards for biologics, serum production expanded rapidly to fight not only diphtheria but a host of other diseases. The advances in treatment and immunization could not have happened without the quiet work of the horses who provided serum. They are largely forgotten now, but in their day, many became famous and widely adored for their contributions to health science. Even into the 1930s, only about half of the horses inoculated would produce antitoxin. Individual horses became heroes for their ability to reliably produce large amounts of potent serum.

References

- Acosta, Anna M., et al. “Diphtheria.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/Pubs/pinkbook/downloads/dip.pdf (accessed July 2, 2021).

- Condran, Gretchen A. “Changing patterns of epidemic disease in New York City.” In Hives of Sickness: Public Health and Epidemics in New York City, edited by David Rosner, 27–41. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press for the Museum of the City of New York, 1995.

- Hunt, Peter B. “The Evolution of Federal Regulation of Human Drugs in the United States: An Historical Essay.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 44.

- Park, William H. “The First Production of Diphtheria Antitoxin in the United States.” Canadian Public Health Journal 27, no. 3.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Report on the Vital and Social Statistics in the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890; Part I—Analysis and Rate Tables. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1896.

- “All Eager for Anti-Toxine.” New York Herald. December 11, 1894.

- “Anti-Toxine Grows in Favor.” New York Herald. December 13, 1894.

- “Antitoxin Inquest.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. November 3, 1901.

- “City Anti-Toxin Given to Babies Caused Deaths.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 30, 1901.

- “Coroner Will Make an Investigation.” St. Louis Republic. October 31, 1901.

- “Emma Mary Ernst is the Eleventh Tetanus Victim.” St. Louis Republic. November 5, 1901.

- “’I Propose to Fix the Responsibility Specifically.’ Mayor Wells at Tetanus Inquiry.” St Louis Republic. December 13, 1901.

- “Its Fund a Success.” New York Herald. December 1, 1895.

- “One Animal at Michigan Laboratory Credited with Saving 75 Human Lives.” Detroit Free Press. August 13, 1933.

- “Ravold’s Helper in Serum Work Tells New Story.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. November 30, 1901.

- “Remedy for Diphtheria.” New York Herald. January 2, 1895.

- “Veterinarian’s View of City’s Antitoxin.” St. Louis Republic. November 12, 1901.