Women in Immunology

Elise Strang L’Esperance: Pioneer in Cancer Prevention

by John S. Emrich

January/February 2012, pages 21–23

For nearly 100 years, AAI members have been at the forefront of advancements in immunology and related disciplines. In this issue, we profile Elise Strang L’Esperance whose legacy included a number of firsts, both in her medical research and in the career distinction she achieved as a woman.

Elise S. L'Esperance

Elise S. L'Esperance

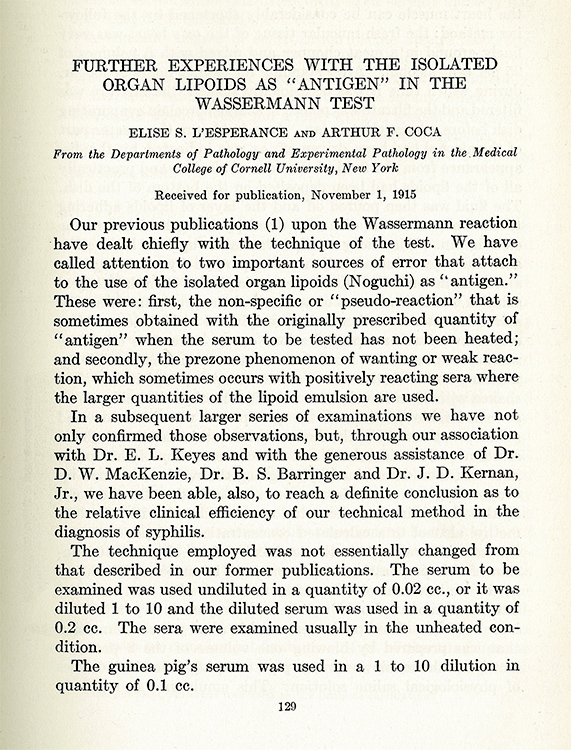

Weill Cornell Medical Center ArchivesIn 1916, Elise L’Esperance, M.D. (AAI 1920), became the first woman to be a lead author on an article published in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). Co-authored with her colleague at the Cornell University Medical College and editor-in-chief of The JI, Arthur Coca (AAI 1916), the article examined sources of error in the Wassermann reaction—the newly developed test for syphilis. This was not the last “first” to be credited to L’Esperance, for she was instrumental in breaking a number of barriers for women in medicine and changing the face of cancer prevention in the United States. For her ground-breaking work in cancer prevention, L’Esperance shared the 1951 Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award with cancer researcher Catherine Macfarlane. L’Esperance and Macfarlane were the first women to be awarded a Lasker for medical research.

L'Esperance-Coca paper

L'Esperance-Coca paper

The Journal of Immunology (1916)Born in 1878, Elise was the youngest of three daughters of Albert Strang, a Yorktown, New York, physician, and Kate Depew Strang, sister of Chauncey Depew, a U.S. senator, lawyer to Cornelius Vanderbilt, and railroad president. Encouraged by her father to pursue a career in medicine, Elise enrolled in the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children (hereafter referred to as New York Infirmary), taking advantage of opportunities created by women’s medical education pioneer Elizabeth Blackwell. While a student, Elise married David A. L’Esperance, a New York attorney, and received her medical degree as Elise L’Esperance, graduating in the college’s final class in 1899.

Early Career

L’Esperance began her medical career as a clinician by interning at Babies Hospital in New York and then entering private practice as a pediatrician, first in Detroit and then in New York City. Frustrated that medicine was unable to spare her patients the ravages of diseases having no known cure, Elise sought to switch her emphasis to medical research. In 1908, she was appointed to the New York Tuberculosis Commission under the esteemed William H. Park (AAI 1916, president 1918–19). As a result of her work with the commission, she became increasingly interested in the research opportunities afforded by a career in pathology. In 1910, she joined the staff of James Ewing, a cancer specialist in the Department of Pathology, Cornell University Medical College, becoming his first female research assistant. William H. Park, 1920

William H. Park, 1920

AAI Collection, UMBC

Elise showed much promise and was promoted to instructor in 1912, awarded a research fellowship to study in Munich, Germany, in 1914, and, in 1920, was promoted to assistant professor—becoming the first woman to attain a professorial rank at the medical school. During this same period, she also served as the director of laboratories of the New York Infirmary. L’Esperance continued to conduct research at Cornell until 1932 and at the New York Infirmary until 1946.

A Clinic for Cancer

In the early 1930s, L’Esperance’s mother succumbed to cancer. Two years later, her cousin Chauncey Depew, Jr., passed away. Having died a bachelor, Depew left a large family inheritance to his cousins, who had already inherited large sums of money from their mother.

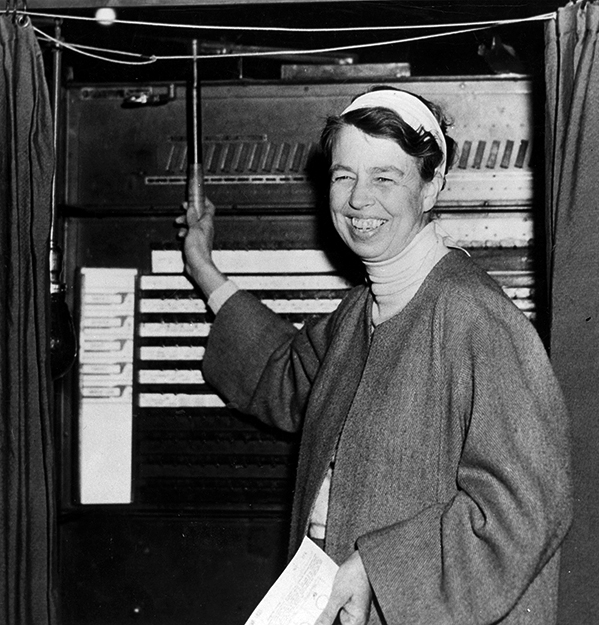

In honor of their mother, L’Esperance and a sister used funds now available to them to create the Kate Depew Strang Clinic for Cancer and Allied Diseases at the New York Infirmary. With new equipment and its own staff endowed by the sisters for the first two years, the clinic was established as a separate department of the hospital. L’Esperance served as its first director, stating that the clinic’s mission was to bring the use of modern techniques to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer in women. At its dedication, Ewing declared that the clinic represented “a pioneer step...devoted to the greatest problem in medicine and probably the greatest hazard in human life—cancer.” On its first anniversary celebration, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt praised the sisters’ “unselfish generosity.”

Eleanor Roosevelt votes, 1936

Eleanor Roosevelt votes, 1936

FDR Library & MuseumShortly after founding the clinic, L’Esperance became convinced that the best way to prevent cancer from developing into malignant tumors lay in its early detection through use of the most modern techniques for physical examinations. The causes of cancer, after all, remained unknown. She would endeavor to enact her “tentative plan to prove whether prevention and early diagnosis” of cancer were effective. If so, she maintained that her approach “could become a practical part of a medical health service.”

Fortunately, L’Esperance had the education, training, and financial resources to act upon her convictions and do something that ultimately proved revolutionary. In May of 1937, she founded the Kate Depew Strang Cancer Prevention Clinic at the New York Infirmary. The goal of this new clinic was to identify early-stage cancers and pre-cancerous conditions because, according to L’Esperance, “effective treatment is that instituted at a time when the process is localized.” The clinic was a first-of-its-kind in the United States in its provision of a “complete physical examination of women, with especial reference to cancer.” The Cancer Prevention Clinic did not treat patients. Patients diagnosed with potential cancer were referred to their personal doctors.

The physical examination at the clinic typically included mouth, nose, throat, pelvic, and rectal examinations, urinalyses, blood tests, and a full-plate x-ray of the chest. L’Esperance remained vigilant in the addition of new techniques as they became available for early detection of the disease. These included a test for diabetes as well as a technique devised by George Papanicolaou to detect cervical cancer (today known as the Pap smear). The latter led to the enduring use of the Pap smear as part of a regular gynecological exam.

The mission of the Cancer Prevention Clinic included educating patients about the importance of routine physical examinations to identify cancer early. The clinic was also committed to alerting patients to what were deemed “predisposing factors” for cancer. Among these factors, L’Esperance included the “excessive use of tobacco and other chronic irritants.”

A Legacy in Prevention

The preventative clinic model L’Esperance created proved so successful in identifying early-stage cancers and pre-cancerous cells that Ewing asked her to create a similar institution at Cornell-affiliated Memorial Hospital. The first clinic opened to women in 1940 and was followed by a clinic for men in 1944. By 1947, when the newly constructed building of the Kate Depew Strang Cancer Prevention Clinic at Memorial Hospital Center was dedicated, cancer was the second-leading cause of death in the United States, as the death rate had continued increasing unabated since the turn of the century. The idea of a cancer prevention clinic was revolutionary in 1932, but, by 1947, it was hailed as “the most powerful tool thus far devised” for the early detection of cancer.

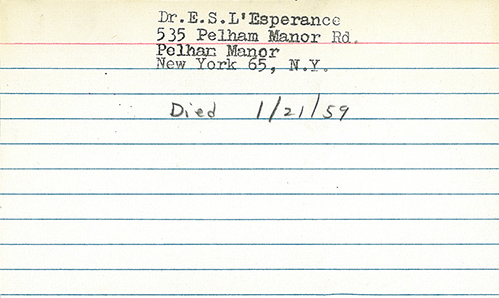

L'Esperance AAI membership record card

L'Esperance AAI membership record card

AAI ArchiveThe preventative clinic model was copied quickly across the country. Clinics opened in Philadelphia (1938) and Chicago (1943). By 1947, 181 clinics had opened in 30 states and in almost every major city across the country.

In addition to the Lasker Award, L’Esperance received the Clement Cleveland Medal of the New York City Cancer Committee in 1942, becoming the first woman to do so. She also served as the first editor of the Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, as well as an associate commander of the Women’s Field Army of the American Society for the Control of Cancer.

References

- L’Esperance, Elise S. “The Early Diagnosis of Cancer.” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 23, no. 7 (1947): 394–409.

- L’Esperance, Elise S. and Arthur F. Coca. “Further Experiences with the Isolated Organ Lipoids as ‘Antigen’ in the Wassermann Test.” The Journal of Immunology 1, no. 2 (1916): 129–158.

- Macfarlane, Catherine. “Cancer Prevention Clinics.” Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association 1, no. 1 (1946).

- U.S. Public Health Service. Vital Statistics of the United States, 1947 Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- U.S. Department of Commerce. Mortality Statistics, 1932. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- “181 Centers Push Fight on Cancer.” New York Times. November 24, 1947.

- “C. M. Depew JR. Left Estate of $6,199,241.” New York Times. November 17, 1931.

- “Clinic Dedicated in Cancer Battle.” New York Times. November 13, 1947.

- “Clinic Praised by Mrs. Roosevelt.” New York Times. April 27, 1934.

- “Depew Will Give $1,000,000 to Yale.” New York Times. April 19, 1928.

- “Dr. L’Esperance Specialist, Dead.” New York Times. January, 22 1959.

- “New Cancer Clinic Opened by Women.” New York Times. April 12, 1933.