Profiles of Black Pioneers in Immunology

Onesimus

In the early 18th century, colonists in New England had to contend with wave after wave of smallpox brought in by trading ships. Onesimus, an African enslaved by the minister Cotton Mather, provided the knowledge that would lead to countless lives saved.

In the early 18th century, colonists in New England had to contend with wave after wave of smallpox brought in by trading ships. Onesimus, an African enslaved by the minister Cotton Mather, provided the knowledge that would lead to countless lives saved.

Mather asked Onesimus if he had had smallpox in Africa. Onesimus described variolation by applying infectious material from a smallpox blister to a small cut in a healthy person’s skin. In fact, he possessed a scar of his own from this practice. The immunity that variolation provided was not perfect, but greatly reduced the risk of the disease.

Mather inquired among his other slaves and discovered that many of them were also familiar with variolation—and that the telltale scar meant a higher price in the slave-market, even though the slavers did not understand the process. He read about the method being practiced in many areas of the world and decided to campaign for widespread variolation in Boston.

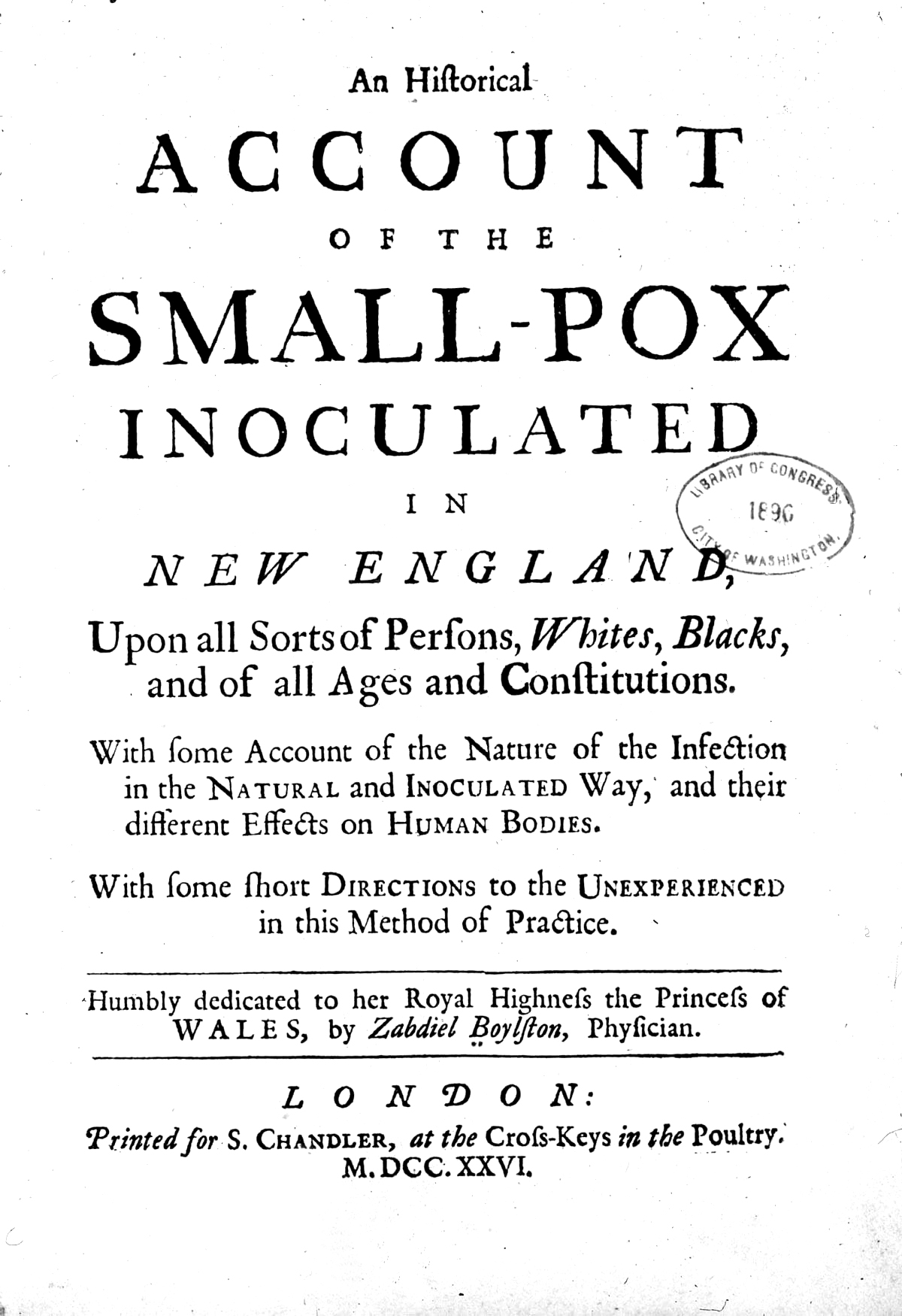

When the next epidemic hit in 1721, one doctor, Zabdiel Boylston, inoculated 242 Bostonians according to Onesimus’s instructions. Half of the population of Boston contracted smallpox, and while one in seven of them died, only one in 40 of the inoculated perished. The clear evidence led to the practice of variolation being accepted widely throughout the colonies and a dramatic decline in the deathrate from smallpox.

William Augustus Hinton

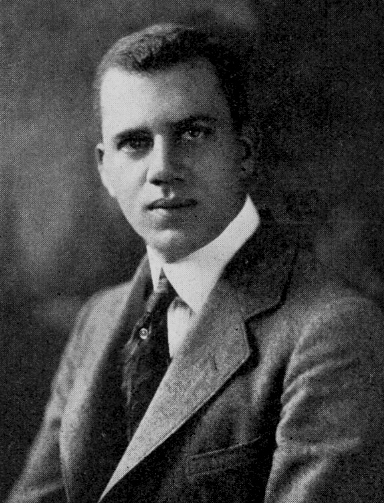

William Augustus Hinton was born in Chicago in 1883 to parents who had grown up enslaved in North Carolina. His father worked as a railroad brakeman in Kansas, making it possible for Hinton to attend the University of Kansas and then Harvard, graduating at the age of 22 with a Bachelor of Science degree. He received his M.D. from Harvard Medical School (HMS) in 1912, but as an African American, was barred from practicing surgery in Boston.

William Augustus Hinton was born in Chicago in 1883 to parents who had grown up enslaved in North Carolina. His father worked as a railroad brakeman in Kansas, making it possible for Hinton to attend the University of Kansas and then Harvard, graduating at the age of 22 with a Bachelor of Science degree. He received his M.D. from Harvard Medical School (HMS) in 1912, but as an African American, was barred from practicing surgery in Boston.

With no internship, he volunteered his time at Massachusetts General Hospital, performing autopsies on syphilis victims. Through this experience, he became an expert in diagnosing and treating syphilis, and became chief of the Wasserman Laboratory at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health in 1915. Three years later he returned to HMS as an instructor and began teaching courses in immunology and bacteriology in 1921. He taught there for the rest of his career, and was the first African American to be made full professor at Harvard when he was promoted in 1949—just a year before he retired.

Hinton’s legacy includes two novel tests for syphilis: a flocculation test in 1927, and then a serological test that became a standard for years, endorsed by the US Public Health Service in 1934. He also established the first laboratory training school for women.

Julian H. Lewis

Julian H. Lewis was one of the first African Americans to earn an M.D.-Ph.D. In the process, he also became the first African American to join the honor societies Sigma Xi, Phi Beta Kappa, and Alpha Omega Alpha. He received his Ph.D. in physiology and pathology at the University of Chicago and then an M.D. from Rush Medical College in 1917. That same year, Lewis became the first Black instructor to teach at the University of Chicago and in 1923 was made assistant professor of immunology.

Julian H. Lewis was one of the first African Americans to earn an M.D.-Ph.D. In the process, he also became the first African American to join the honor societies Sigma Xi, Phi Beta Kappa, and Alpha Omega Alpha. He received his Ph.D. in physiology and pathology at the University of Chicago and then an M.D. from Rush Medical College in 1917. That same year, Lewis became the first Black instructor to teach at the University of Chicago and in 1923 was made assistant professor of immunology.

In 1942, Lewis boldly challenged the race-based blood-typing theories of the day in his book The Biology of the Negro. It was the first book to put forth a scientific argument refuting the idea of a superior race. The next year, he left the university for a position at Chicago’s Provident Hospital, the first Black-owned and operated hospital in America.

Throughout his career, Lewis acted as a mentor and advisor to numerous Black Chicagoans. His portrait was commissioned in 2015 and donated to the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American history and Culture.

Ellamae Simmons

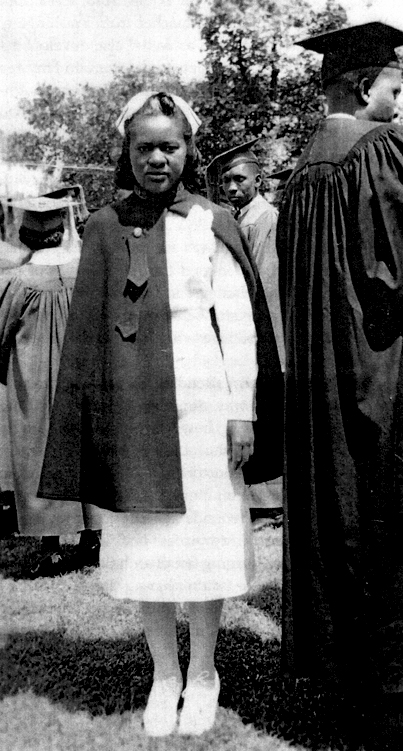

Ellamae Simmons spent her life breaking barrier of segregation in both scientific and social arenas. She wanted to attend Ohio State University in 1936 but was told that the school’s housing would not accommodate a Black woman. She went to Hampton nursing school instead, and served in the Second World War as one of the first African Americans to integrate the US Army Nurse Corps.

Ellamae Simmons spent her life breaking barrier of segregation in both scientific and social arenas. She wanted to attend Ohio State University in 1936 but was told that the school’s housing would not accommodate a Black woman. She went to Hampton nursing school instead, and served in the Second World War as one of the first African Americans to integrate the US Army Nurse Corps.

After the war, Simmons went back to OSU and became that first Black woman to live in the university’s dorms while she completed a pre-med degree. She received her M.D. from Howard University in 1959.

Simmons was the first African American woman to specialize in asthma, allergy, and immunology, as well as the first—in 1964—to join the medical staff at Kaiser Foundation Hospital. Three years later, she bought a house in the then-white-only Presidio Heights neighborhood of San Francisco.