Profiles in Leadership / Formative Years

The Short and Influential Life of Richard Weil

by Charles Richter and John Emrich

December 2019, pages 33–37

Richard Weil

Richard Weil

UMBCOn November 19, 1917, Richard Weil, an accomplished and highly regarded young physicianscientist and third president of The American Association of Immunologists (AAI), was cut down in his prime by pneumonia at Camp Wheeler, a U.S. Army training facility near Macon, Georgia. In his last weeks, Major Weil had worked tirelessly to fight successive, overlapping epidemics of measles and pneumonia among the World War I draftees, mostly rural and fresh off the train, until he finally succumbed himself. At its next meeting in March 1918, the AAI Council issued a resolution expressing sorrow and honoring Weil for both his “unwearying labors in his chosen field” and his untimely death in the line of duty.

Childhood and Education

Merchant's Exchange Building, NYC

Merchant's Exchange Building, NYC

New York Historical SocietyBorn in 1876, Richard Weil came from a well-to-do family with many ties to New York City society and the local Jewish community. Both of his parents had immigrated to the United States from Bohemia in the early 1850s and quickly found comfortable employment. Leopold Weil was a broker at the United States Custom House, and his wife Matilda ran a prominent Jewish girls boarding school.

“Mrs. Leopold Weil’s School” educated students from wealthy families all over the country in English, French, German, and Hebrew. Richard was the seventh of eight Weil children who grew up in a series of houses on the Upper West Side of Manhattan that also served at various times as Matilda's classrooms and as home to her extended family, several student boarders, and a sizable domestic staff.

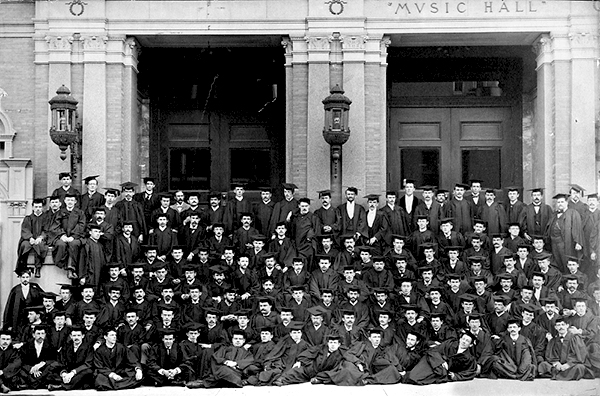

A gifted student, Weil matriculated at Columbia University where he earned an A.B. at 20 years of age. He immediately continued on to the College of Physicians and Surgeons where he earned his medical degree in 1900. Upon graduation from medical school, Weil began a two-year residency at the German Hospital in New York City. He then travelled to Europe where he continued his training in laboratories and clinics at the universities of Vienna and Leipzig.

Weil's graduation class at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in front of Carnegie Hall, 1900

Weil's graduation class at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in front of Carnegie Hall, 1900

Columbia University Irving Medical Center Archives and Special Collections

Shortly after returning to New York City in 1904, Weil married Minnie Straus, the daughter of Macy’s co-owner Isidor Straus. His return also coincided with accepting a position at Cornell University Medical College (now Weill Cornell Medicine). He taught and conducted research there and held concurrent positions at various hospitals in the city from 1905 until 1917, when he enlisted in the U.S. Army.

Early Scientific Successes

Isidor Straus and family; Richard and Minnie Weil are on the right

Isidor Straus and family; Richard and Minnie Weil are on the right

Straus Historical SocietyUpon returning from Europe, Weil’s early research in serology quickly gained the attention of scientists in New York City and around the country. His publications appear diverse—cancer, cobra venom, and blood transfusions—but were fundamentally an exploration of understanding hemolysis. He investigated methods to identify evidence of early stages of cancers circulating in the blood and the effect of cobra venom on human blood, and was the first to demonstrate the feasibility of “icebox” (refrigerated) storage of blood for transfusion.

Cancer, however, was the primary focus of his early research. In addition to his work on devising a blood test for cancer, he examined the hemolytic reactions of cancer, tumor immunology in rats, and the effects of novel experimental cancer treatments including radium. Owing to his investigative work, Weil became a charter member of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) in 1907.

By 1912, Weil's focus began to pivot away from cancer towards anaphylaxis. Although he still authored the occasional article on cancer research, the preponderance of his publications until his death related to his ongoing experiments supporting the cellular mechanisms of anaphylaxis. His findings ran counter to the humoral theory then dominating American scientific thought. His 22-part series on the topic, which only ended upon his enlistment in the Army, proved prescient as discoveries in the 1960s verified the cellular mechanism of anaphylaxis. The series also proved influential to a new field of science—immunology—as the editors of The Journal of Immunology (The JI) selected parts 14 through 17 as the first articles published in its inaugural issue.

The Beebe Affair

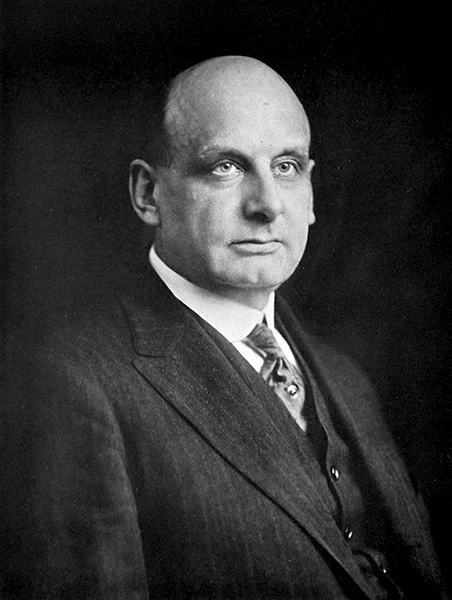

Silas P. Beebe, ca. 1908

Silas P. Beebe, ca. 1908

American Association for Cancer ResearchFollowing his early successes, Weil found himself thrust into the national scientific spotlight when he became embroiled in controversy over a purported cancer treatment at Cornell. In 1915, he was involved in a trial on the validity of “autolysin,” a “liquid extract of vegetable origin” as a cancer cure. The primary investigator of the initial study in 1912 was Silas P. Beebe, a Cornell physiological chemist and a founder of the AACR. Beebe claimed the miracle drug could, with just a few injections, produce “consistent improvement” in inoperable and previously incurable cancers. He also announced—in the pages of the New York Times—his intention to move forward with the treatment commercially.

Weil’s demonstration that autolysin was not a credible treatment for cancer, coupled with Beebe’s push to commercialize the drug, resulted in Cornell asking Beebe to resign from his position as professor of experimental therapeutics, and the department was abolished. Furthermore, scientific societies asked for his resignation or no longer published his science.

Following Beebe’s departure, Weil found himself the target of numerous inquiries about the promised effects of autolysin. In response, he published a scathing rebuttal in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), showing that—contrary to Beebe’s claims—of 23 patients in the study, 14 died in the hospital, eight were discharged with no improvement, and only one saw any improvement. That patient, like the rest, had also been given Roentgen ray treatment. Out of a job, Beebe was enraged by the challenge and excoriated Weil in JAMA, accusing him of “willfully misrepresent[ing]” the study and not “acting solely from good motives.” Because autolysin possessed none of the capabilities Beebe had ascribed to it, Weil emerged from the imbroglio with increased national credibility as a scientist.

AAI and The JI

In addition to his research, Weil offered his service to scientific societies. He was instrumental in recruiting early AAI members and helping select the initial editorial board of The JI in 1915. The next year, he became the founding editor of AACR's The Journal of Cancer Research, the first English-language cancer journal. Weil also served as the third president of AAI (1916–1917). In keeping with the bylaws at the time, Weil was to serve on the AAI Council until 1924, but when the United States officially joined the First World War on April 6, 1917, he resigned his position and was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army Medical Corps.

His first posting at Fort Benjamin Harrison, northeast of Indianapolis, Indiana, was brief. He was quickly promoted to major and detailed to Georgia's Camp Wheeler

as the chief of medical staff. At Wheeler, a newly constructed U.S. Army National Guard mobilization and training camp near Macon, Weil experienced a world vastly different—scientifically and socially—from New York City.

The Great War and Camp Wheeler

Camp Wheeler was a temporary 21,000-acre tent camp rapidly built on drained swampland in the spring and summer of 1917. The training camp and mobilization center, which opened in August, housed both white and black men from Georgia, Alabama, Florida, and parts of Virginia.

Most of the recruits came from rural areas where they were less likely than soldiers from cities to have been exposed to many communicable diseases. At the same time, they were more likely to be infected by endemic parasites, such as hookworm, that compromised their immune systems.

When Macon’s coldest winter in 40 years hit, the Army was unprepared: the men were not equipped with sufficiently warm clothing, the camp lacked winter tents, and conscripts were kept in close quarters at all times to keep warm.

From left: Vaughan, Gorgas, and Welch

From left: Vaughan, Gorgas, and Welch

University of MichiganBecause of this, Wheeler was presented with significant challenges to preventing communicable diseases, like the flu.

These conditions collectively paved the way for a serious outbreak of measles at the close of 1917. According to Colonel Victor C. Vaughan (AAI 1915), then the chief of the Army’s Division of Communicable Diseases, “Not a troop train came into Camp Wheeler…in the fall of 1917 without bringing from one to six cases of measles already in the eruptive stage.” In addition, 60–70% of recruits were infected with hookworm, which often results in vitamin A deficiency that increases susceptibility to both measles and pneumonia. The measles patients not only had weakened immune systems, but they also were brought together in the hospital tents where their coughs could further spread pneumococcus. It was a perfect storm for igniting an epidemic.

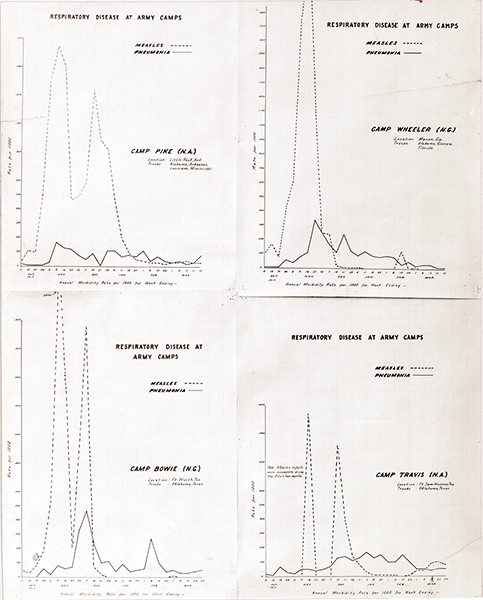

Among the approximately 20,000 recruits at the camp, there were 522 cases of measles in October 1917, and 2,421 the next month. In this already compromised population, an epidemic of pneumonia struck next, with 84 cases in October and 452 in November. About a quarter of the men admitted with pneumonia in these two months died. Conditions in the camp were bad enough that in Macon, rumors began flying of dozens of men dying in a single night.

Weil dedicated himself tirelessly to caring for the sick, but by November 11, 1917, he had fallen ill himself. When word of Weil’s illness reached his home in New York, his wife Minnie immediately traveled to Georgia with a specialist from New York to be by his side and assist in his care. Also present on the medical staff was a fellow AAI member, Ernest G. Stillman (AAI 1930), who had been sent to Wheeler to help fight the pneumonia epidemic. Weil’s condition quickly worsened, however, and he died after eight days of illness.

The governors of two states made visits to Wheeler to investigate claims of poor medical facilities. Both Governor Hugh Dorsey of Georgia, who toured the camp while Weil lay on his sickbed, and Governor Charles Henderson of Alabama, who arrived the week after Weil’s death, found that under Weil, the medical staff had performed admirably.

Camp Wheeler, Macon, GA, 1918

Camp Wheeler, Macon, GA, 1918

National ArchivesOn November 23, Surgeon General William C. Gorgas, accompanied by William H. Welch and Victor C. Vaughan, arrived at the camp to evaluate the medical situation. By this time, additional medical staff had also been brought in. There were now 280 doctors battling the epidemics at Wheeler. Gorgas explained to a concerned press that the cause of the measles epidemic was a lack of “resisting power” to the disease among the new recruits from rural areas who had not previously been exposed. He added that “a young man who wants to be a soldier should contrive to have his measles when he is a child.”

Out of all the U.S. Army camps in 1917, Wheeler had the highest rates of admissions for measles and lobar pneumonia, leading to the second highest death rate in the Army and National Guard. To combat epidemics at the camps hardest hit by these diseases, Army medical staff began to keep patients separated in cubicles formed by sheets hung from frames between their beds. This practice proved successful enough that the Surgeon General’s office recommended that it be continued and used more generally—an important innovation when the influenza pandemic hit the next year.

Influenza

Prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, influenza was not a reportable disease in the general public, but the Army began to track the number of influenza cases among the troops as soon as the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917. Most training camps saw hundreds of unremarkable cases that year, like any other flu season. At Wheeler, there were 685 cases of influenza in the last three months of 1917, but none produced complications and not a single man died.

Army morbidity rates for measles and pneumonia at training camps, 1919

Army morbidity rates for measles and pneumonia at training camps, 1919

National ArchivesThe influenza pandemic began quietly on March 4, 1918, at Camp Funston in Kansas, among men from nearby Haskell County. By April, and half a country away, 1,967 cases of influenza were reported at Wheeler—a few with complications—but there were still no fatalities from the disease. In the late spring of 1918, this initial spike in cases was not seen as the first wave in a global pandemic, but the official report from the Surgeon General described it as an epidemic. When the most significant wave of pandemic influenza came in autumn of 1918, Camp Wheeler was relatively well prepared for it.

Hoping to stave off a repeat of the autumn 1917 pneumonia epidemic, Russel L. Cecil (AAI 1920) and Henry F. Vaughan went to Wheeler in September 1918 to begin a large study on prophylactic vaccination for pneumonia. They vaccinated 13,460 men against pneumococcus Types I, II, and III, and were able to demonstrate an effective immune response before their work was cut short by the appearance of influenza. Notably, their research showed that while overall mortality from pneumonia was significantly lower among those vaccinated, mortality from pneumonia secondary to influenza was unaffected.

Initially, the camp was placed under quarantine following reports of influenza both in the local civilian population and at other military camps. Nationwide, 40,000 cases of influenza among soldiers had been reported by the end of September. Up to that point, Wheeler was publicly considered free of influenza, but on the 28th of the month, camp officials acknowledged that their first cases had been admitted to the base hospital.

The lessons learned in the measles and pneumonia epidemics of 1917 seem to have had a positive effect on Wheeler’s preparedness for pandemic influenza. Having already experienced one of the worst battles with communicable disease among all the Army camps, Wheeler’s medical staff was practiced at identifying and isolating patients who displayed dangerous symptoms.

Exact comparisons to other camps are unfortunately impossible; unlike their counterparts at the vast majority of Army camps, Wheeler’s physicians made an official diagnosis of influenza only upon a laboratory finding of Pfeiffer’s bacillus (Haemophilus influenzae [then known as Bacillus influenza]), at the time thought to be the cause of influenza. Because the bacterial infection does not always present in every instance of influenza, this practice would have ignored many actual cases of the disease.

Temple Emanu-El, 5th Ave. and 43rd St., ca. 1860s

Temple Emanu-El, 5th Ave. and 43rd St., ca. 1860s

Temple Emanu-ElEven with this administrative discrepancy, however, the records show that Wheeler experienced significantly lower than average rates of admission and death for all respiratory diseases in 1918.

Tribute to Richard Weil

Richard Weil’s funeral was held with military honors at Temple Emanu-El in Manhattan on November 23, 1917. The respect the young physician-scientist commanded among his peers was evident in the men who served as his honorary pallbearers. They included Rufus Cole (AAI 1917, president 1920–21), director of the Rockefeller Institute; William M. Polk, dean of the medical school at Cornell; William B. Coley, father of cancer immunotherapy; and Arthur F. Coca (AAI 1916, The JI editor-inchief 1916–48); as well as several other prominent physicians, scientists, businessmen, and bankers.

Weil is remembered for his remarkable and selfless service to his country and his seminal contributions to the field of immunology. His service during World War I and his efforts to address Camp Wheeler’s medical problems demonstrated the important role immunologists played during this challenging period.

See related published articles:

References

- Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Penguin, 2004.

- Beebe, Silas P. “Correspondence: The ‘Autolysin’ Treatment for Cancer.” Journal of the American Medical Association 65, no. 25 (1918): 2185.

- Beer, Edwin and Cary Eggleston. “Major Richard Weil, M.O.R.C.” The Journal of Immunology 3, no. 1 (1918): i–vii.

- Cecil, Russell L. and Henry F. Vaughan. “Results of Prophylactic Vaccination against Pneumonia at Camp Wheeler.” Journal of Experimental Medicine 29, no. 5 (1919): 457–83.

- Emrich, John S. “Founding The Journal of Immunology.” AAI Newsletter, February 2016: 16–20.

- Kolmer, John A., Martin H. Synnott, and A. Parker Hitchens. “Resolutions upon the Death of Dr. Richard Weil.” 30 March 1918. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Litzinger, Mary. "“Studies in Anaphylaxis”—The First Article in The Journal of Immunology." AAI Newsletter. December 2011: 18.

- Weil, Richard. “Sodium Citrate in the Transfusion of Blood.” Journal of the American Medical Association 64, no. 5 (1915): 425–6.

- Weil, Richard. “The Autolysin Treatment for Cancer.” Journal of the American Medical Association 65, no. 19 (1915): 1641–44.

- “Alabama Delegation Visits Camp Wheeler.” Cullman Tribune. 30 November 1917.

- “Alabama Men Inspect Soldiers at Camp Wheeler.” Montgomery Times. 24 November 1917.

- “Camp Wheeler.” Georgia Historical Society. https://georgiahistory.com/ghmi_marker_updated/camp-wheeler (accessed December 18, 2019).

- “Cancer Remedy Puts Beebe Out of Cornell.” New York Times. 21 October 1915.

- “Charter Members of the American Association for Cancer Research: 1907,” American Association for Cancer Research. https://www.aacr.org/Documents/AACR_Charter_Members.pdf (accessed December 18, 2019).

- “Dorsey Finds Men Are Well Treated at Camp Wheeler.” Atlanta Constitution. 17 November 1917

- “Founders of the AACR: Silas P. Beebe.” American Association for Cancer Research. https://www.aacr.org/AboutUs/Pages/aacr-founders-silas-p-beebe.aspx (accessed December 18, 2019).

- “Investigation Most Thorough.” Atlanta Constitution. 17 November 1917

- “Major R. Weil Dies at Camp Wheeler.” New York Times. 20 November 1917.

- “Redouble Efforts to End Camp Disease." Logansport Pharos-Tribune. 19 November 1917.

- Report of the Surgeon General of the Army to the Secretary of War for 1918. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918.

- Report of the Surgeon General of the Army to the Secretary of War for 1918. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919.

- “Richard Weil.” Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936.

- “See Hope in New Cancer Remedy.” New York Times. 16 May 1915.