Formative Years

The Founding of AAI

by John S. Emrich

May/June 2012, pages 24–29

University of Minnesota, c.1908

University of Minnesota, c.1908

Library of CongressOn the unusually warm evening of June 19, 1913, far from the national spotlightor any mention on the front pages of newspapers, a small group of physicians met on the campus of the University of Minnesota to form a society for a new medical specialty. This new society would help define immunology as bona fide area of specialization and would eventually become The American Association of Immunologists (AAI), the preeminent professional association for the discipline in the world.

These physicians had been attending the annual meeting of the American Medical Association and were meeting  Martin J. Synnott

Martin J. Synnott

AAI Collection, UMBCat the invitation of Martin J. Synnott (AAI 1913, secretary 1913–18), a private practice physician from Montclair, New Jersey, who had made previous, failed attempts to organize a society of North American disciples of Sir Almroth Wright (AAI 1914).

On this day, however, he was finally successful, and The American Association of Immunologists (AAI) was founded. The new society quickly organized around a definitive name, a set of objectives, and leadership that would build the foundation for lasting success. In just a few years, the new society would lead in legitimizing a new scientific discipline as the group established its own annual meeting and created what was to become the most highly acclaimed peer-reviewed scientific journal in its field, The Journal of Immunology (The JI).

Wright’s Disciples

Sir Almroth Wright

Sir Almroth Wright

AAI Collection, UMBCThe idea to form a new professional organization had first occurred to Synnott in early 1912. As a former student of Wright, Synnott wanted to bring together the men in the United States and Canada who had trained with Wright and shared his vision of the emerging promise of vaccine therapy. In 1912, Synnott wrote to 49 former students of Wright’s and received 40 favorable responses to his proposal for forming “The Society of Vaccine Therapists.” These 40 physicians were in practice located across the continent, isolated from other colleagues schooled in Wright’s premise that “the physician of the future would be a vaccine therapist.” Wright’s “disciples” were not sufficiently organized in any fashion to promote awareness of the promise held by vaccine therapies.

Praed Street Lab, 1906

Praed Street Lab, 1906

AAI Collection, UMBCWright was the founder and director of the Inoculation Department at St. Mary’s Hospital in London and the Praed Street Laboratories. His laboratories were focused on the concept that “recovery from all infective diseases must be largely determined by the development of ‘antibodies’ in the patient’s blood and that this process could be probably stimulated by inoculation of the appropriate vaccine.” Wright advocated for more than mere vaccination, promoting a technique of vaccine therapy that he had developed. The therapy was based upon the premise that a sick patient could be injected with appropriate levels of a vaccine to “exploit the uninfected tissue in favor of the infected.” His initial success in the early 1900s with an effective anti-typhoid inoculation technique had made the Praed Street Laboratories a magnet for new students. This inoculation technique was adopted by the British War Department in 1914 as standard procedure. Its success had earlier led to Wright’s being inducted into knighthood.

A Society of Vaccine Therapists

Despite the British military’s adoption of his inoculation technique and his 1906 induction into knighthood, Wright’s vaccine therapy research in 1912 was not appreciated or widely employed outside of England. Synnott’s efforts to form the new Society of Vaccine Therapists were intended to promote awareness of the field’s promise. Despite the 40 positive responses Synnott had received for the concept of the new society in 1912, too few of his colleagues were available for the proposed organizational meeting. He soon made another attempt, calling for a meeting on the evening of May 5, 1913, at the Hotel Raleigh, Washington, DC, during the annual meeting of the Association of American Physicians. Still, there were too few participants. Undeterred, Synnott scheduled the successful Minneapolis organizational meeting from which the new professional society emerged that summer.

In Synnott’s view, it was a society of vaccine therapists. The scope and membership of the new society formed at the meeting, however, departed significantly from Synnott’s initial concept, encompassing a broader view of the science and clinical practice. This difference was reflected in the name of the new society: The American Association of Immunologists.

Gerald B. Webb

Gerald B. Webb

AAI Collection, UMBCThe name is attributed to Gerald B. Webb (AAI 1913, president 1913-15), a nationally renowned tuberculosis physician and researcher who would become the first president of the society. Although he had trained with Wright and was a devoted disciple, he was concerned that Synnott’s proposed Society of Vaccine Therapists would impose restrictions on future growth of the new organization. For Webb, linking a society exclusively with vaccine therapy posed two major problems. First, he was aware that Wright’s theories and methods were viewed with skepticism in England and Europe, and he sought to avoid this tarnish. Second, restricting a society to a single process would limit its interest. If the new society was perceived as anchored only in vaccine therapy, Webb feared it would not attract clinicians and researchers in other related, growing fields, such as experimental pathology. To make the society more inclusive and flexible, the founders expanded the list of eligible members to include physicians and researchers who had trained with Élie Metchnikoff, Paul Ehrlich, August von Wassermann, as well as in “other famous laboratories in Europe.” They also sought a name for the organization that would connote a broader mission and position the society for growth with scientific and medical advances. They settle upon using a new term, “immunology,” in the name.

A New Scientific Field

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “immunology” had entered the English language through its use by two future AAI members and presidents shortly before the founding of AAI. In 1909 Ludvig Hektoen (AAI 1919, president 1926–27) was the first to use the word. He did so in his article, “Opsonins and Other Antibodies,” in Science.

Hektoen used the term only once – and only in passing – when referring to the law of opsonin production: “In the language of immunology any substance capable of giving rise to antibodies in suitable animals is called an antigen.” Then, a mere three months before AAI was formed, Frederick P. Gay (AAI 1918, president 1921) defined immunology as a distinct scientific discipline in the Journal of the American Medical Association. In his article, “Immunology: A Medical Science Developed through Animal Experimentation,” Gay asserted that “[t]he science of immunity, or immunology, would explain the mechanism by which the animal body is enabled to resist disease.”

In 1913, Webb was well aware of Wright’s 1909 proclamation that “the physician of the future will be an immunisator,” and, as his biographer makes clear, Webb preferred Gay’s broad definition of “immunology” to the narrow denotation of Wright’s “immunisator,” referring very specifically to an immunizer, inoculator, or vaccine therapist. Nearly 65 years later, the wisdom of Webb’s preference was praised for its importance to the recognition of immunology as a scientific discipline when David W. Talmage (AAI 1954, president 1978–79) stated, “I believe we can properly attribute [immunology’s] prominence in our vocabulary, if not its invention, to Dr. Webb.”

The Mission Statement

Beyond naming the new society at the founding meeting, the members also created a mission statement in the form of three objectives. The first two reflected the inclusiveness s forth with the use of “immunology” in the name. “To unite the physicians of the United States and Canada who are engaged in the scientific study of immunology and bacterial therapy. To study the problems of immunology, and to promote by its concerted efforts scientific research in this department.” The third objective clearly stemmed from Synnott’s intention to promote awareness of Wright’s teachings: “To spread a correct knowledge of vaccine therapy and immunology among general practitioners.” The dues of the association, to be fixed annually by the Council, were “not to exceed Five Dollars ($5.00).”

Requirements for election to the membership were established. A candidate had to be nominated by one member, be endorsed by two additional members, have provided the AAI secretary with “papers” that indicated the character of his or her contributions to immunology, and have “at least one published contribution to the science of immunology.” The candidate had to be a “graduate of medicine,” although no specific degree requirements were mentioned.

The officers elected during the 1913 meeting were Webb (president), Synnott (secretary), George W. Ross (vice-president), Willard J. Stone (treasurer), and five councillors, including A. Parker Hitchens (chairman of the council), Oscar Berghausen, Campbell Laidlaw, Henry L. Ulrich, and J.E. Robinson. The officers set a date and location for their next meeting, the first AAI annual meeting: June 1, 1914, in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

The First Annual Meeting

Although the date was eventually moved to later in the month, 18 of 52 initial AAI members did, in fact, convene for the first annual meeting of the society on June 22, 1914, at the Hotel Chelsea in Atlantic City. According to the minutes of the first annual meeting, “the work of developing the society had progressed slowly but effectively” since Minneapolis. Membership in AAI had increased from its 52 initial members to 59 with the election of seven new scientists at the meeting. The leadership was kept in place as all of the officers were re-elected, and a draft of the constitution and by-laws was proposed to provide organizational stability. The impetus for future growth, however, was provided by the interesting science presented at this first annual meeting and the founders’ creativity in plans for membership development.

Attendees at this meeting discussed a range of diverse topics during the one-day conference. Presented at the meeting were a few papers on techniques or hypotheses that would not be borne out by later experimentation and that would not be considered “immunology” by today’s standards, but several of the speakers presented studies and technical innovations that did presage the ultimate focus of the field (See “Science at the First AAI Annual Meeting.”)

The members at this first meeting may have had little experience in membership development, but they did not lack imagination for novel ways to enhance the prestige of membership in the society. They established two discretionary membership classes defined vaguely enough to convey member status on a group of prestigious British physicians focused on vaccine therapy at St. Mary’s Hospital. The first of these special membership classes created was the Honorary Member category, to which they elected Almroth Wright and Captain S. R. Douglas. The second category was that of Corresponding Member, to which they elected Alexander Fleming and John Freeman.

Of the 59 Charter Members, the majority were clinicians or professors, and, in keeping with the trend prior to the Second World War, there were very few, if any, Ph.D.s; most, if not all of the Charter Members, were M.D.s. The association had a broad geographical reach and included members from as far north as Toronto, Canada, and as far south as Temple, Texas; from as far east as Boston, Massachusetts, and as far west as Honolulu, Hawaii. The Philadelphia region boasted the most early members (12), followed by New York City region (11), and Ohio (7). The Charter Members also included a constituency that would have been anathema to the vehemently antisuffrage Wright: two women.

A Growing Association

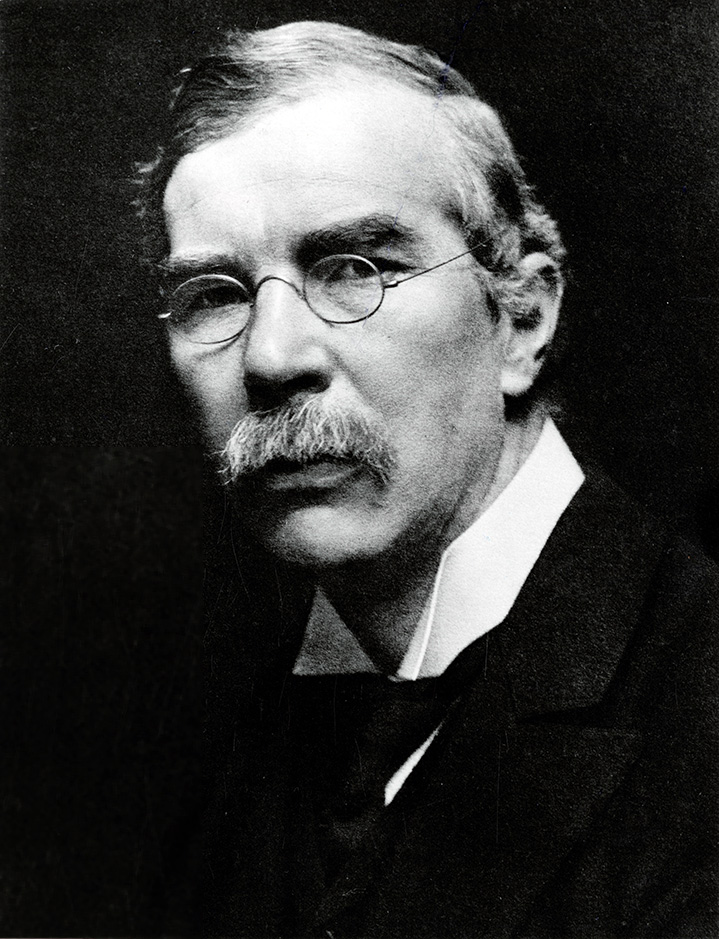

Richard Weil

Richard Weil

AAI Collection, UMBCGrowth of the new society was robust enough that, by the time of that first annual meeting in Atlantic City, even Synnott seems to have accepted the utility of Webb’s preferred term of “immunologist” over “immunisator.” When asked to offer attendees an account of the founding of the society, Synnott took liberties in paraphrasing Wright’s famous assertion, stating that “the physician of the future would be an immunologist,” and that the new society “would in a few years be one of the most important medical organizations on this continent.”

Though Webb is often cast as the most important founding member, two less heralded Charter Members were equally important to the continued success of the new society: A. Parker Hitchens (AAI 1913, Council president 1913–17) and Richard Weil (AAI 1914, president 1916–17). As the president of the Council, Hitchens drafted the first AAI Constitution and By-laws, which established how the organization was to be governed. He was also almost solely responsible for making sure that AAI was a co-founder of The Journal of Immunology with the New York Society for Serology and Hematology (see AAI Newsletter, Dec. 2011) .

Weil had an equal, if less obvious, impact on the association during his abbreviated membership. He was a Charter Member and served as AAI president from 1916 to 1917, but his most enduring contributions to the society were in his recruitment of members and his early assistance to The JI.

Shortly before his retirement, Arthur Coca (AAI 1916, secretary-treasurer 1918–45, editor-in-chief 1920–48) singled out Weil, praising him for having “used his considerable influence to induce outstanding immunologists to join [AAI].” Coca also recalled Weil’s “more optimistic” view of the new journal, which led him to contribute four papers for the first issue. Weil’s papers, in Coca’s estimation, “helped materially” to start the journal. Further, Coca credited Weil for his role in selecting the initial editorial board for The JI. The founders of AAI were enjoying great momentum, but all of their good efforts were soon to be abruptly interrupted.

Facing a World at War

On April 6, 1917, while AAI members were in New York City for their fourth annual meeting, they learned that the United States Congress had declared war on Germany. The “war to end all wars,” which had been raging in Europe for almost three years, had now become a reality for America, and her citizens quickly mobilized for war. As in all other areas of American life, the war had an immediate and lasting impact on the nascent society.

On the same day that they learned the United States had entered the First World War, members of the AAI Council passed the following resolution of shared sacrifice:

Whereas the Government of the United States may soon need the services of trained bacteriologists and immunologists and the facilities of their respective laboratories,

Be it Resolved, that the American Association of Immunologists in meeting on April 6th and 7th, 1917, as a body and as individuals, offer their services and the facilities of their laboratories to the Federal and respective State governments; and,

Be it further Resolved, that the secretary of the American Association of Immunologists send a copy of this resolution to the Secretary of War.

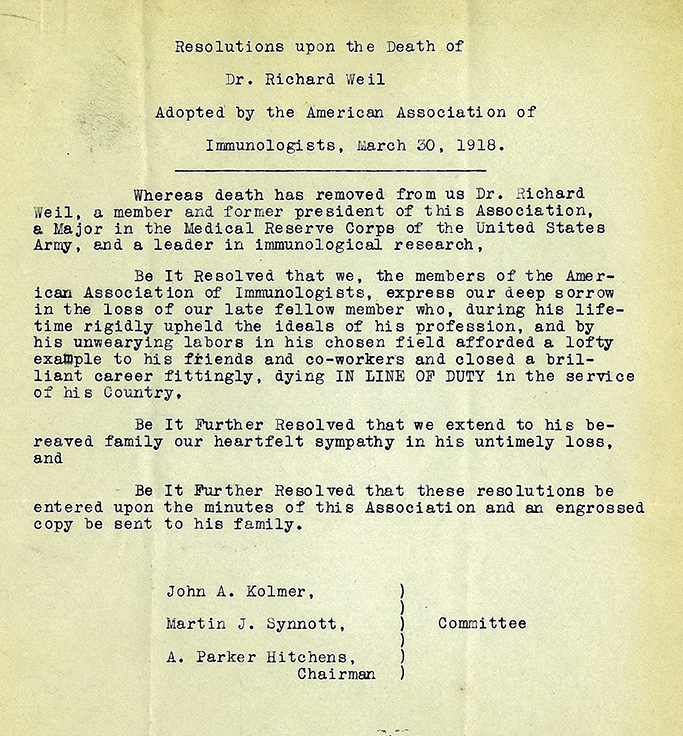

Weil Resolution of AAI Council, March 30, 1919

Weil Resolution of AAI Council, March 30, 1919

AAI ArchiveMany members of AAI and others in the medical and scientific community quickly joined the war effort. AAI President Weil was among them. A number of members stayed in their laboratories to carry out wartime research, while others enlisted in the U.S. Army Medical Reserve Corps and were sent to bases around the country.

The focus of the laboratories in wartime shifted to meet the needs of the military, conducting research into the pandemic influenza, trench diseases, and wound-related infections. Wartime mobilization also directly affected the society’s leadership. Willard Stone had to relinquish his duties as AAI treasurer when he was stationed at the base hospital at Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1917. And Weil was assigned first to Fort Benjamin Harrison near Lawrence, Indiana, and then to Camp Wheeler, outside of Macon, Georgia, as chief of medical service to help quell an outbreak of measles and pneumonia at the camp. Tragically, Weil died of complications from pneumonia on November 19, 1917, only a few months after arriving at the camp. He was the only AAI member to die during the war, but his death dealt AAI a profound loss. At its fifth annual meeting in 1918, AAI passed a resolution honoring his legacy.

Fulfilling the Vision

The year 1920 marked another important year in the history of AAI. It was in that year that the New York Society for Serology and Hematology (SSH) and AAI were merged. SSH had “omitted its monthly meeting for over a year and, since the function of the societies had been in a measure superseded by the American Association of Immunologists, it was deemed advisable to consolidate the societies.” Its members were provided the option of AAI membership. This event added significantly to the size of the organization by adding a number of SSH members to the AAI rolls. The absorption of SSH by AAI eliminated the only other organization in the United States “having interest in immunological matters.” Additionally, The JI became the “property and official organ” of AAI.

By the close of 1920, AAI boasted a membership of 152 physicians and scientists from 22 states, the District of Columbia, and Canada, including 16 women members. The membership included the preeminent American scientists and physicians Simon Flexner, Theobald Smith, Oswald Avery, Hans Zinsser, Rufus Cole, Victor Vaughan, William H. Park, Anna Williams, Elise L’Esperance, and George McCoy (the first director of the National Institutes of Health). Within the next ten years, the membership was to include Karl Landsteiner, Hideyo Noguchi, Karl F. Meyer, Paul DeKruif, and Béla Shick.

AAI was now fulfilling Webb’s and other founders’ earliest vision for the society. The membership was inclusive and flexible, with clinicians, researchers, and public health scientists. With the successful founding of AAI and the preeminence of The JI, the standing of immunology as a distinct discipline of science was broadly recognized by the 1920s.

AAI Today

Today, AAI is the largest, most prestigious professional association for immunologists worldwide, with approximately 7,500 members in 60 countries. The society fulfills its founders ideals in today’s mission to “promote by its concerted efforts scientific research” in immunology through a dedication to advancing the knowledge of immunology and its related disciplines, fostering the interchange of ideas and information among investigators, and addressing the potential integration of immunologic principles into clinical practice. Since the society’s founding 99 years ago, 27 AAI members have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 50 have received Lasker Awards, and three have been awarded the Kyoto Prize.

The Journal of Immunology has maintained a level of noted prominence in the field—if not all of bioscience—for almost one century. As the largest journal in the field, it has been dedicated to consistently featuring important and innovative research across a breadth of topics. With over 150 editors and 4,000 volunteer reviewers, The JI provides full peer review for the more than 3,500 manuscripts submitted annually.

The AAI annual meeting has evolved from 60 earnest scientists meeting for one day in Atlantic City to over 3,500 scientists meeting for 5 days in selected major cities around the United States. In 2011, 1,768 scientific abstracts were presented; 160 speakers were featured in symposia and other sessions; 130 scientific companies occupied the exhibit floor; and galas receptions, and parties were held almost every evening.

Every year, hundreds of AAI members work on behalf of their colleagues as members of the Editorial Board of The JI, session chairs at the annual meeting, speakers and course instructors, and members or chairs of committees.

The association is overseen by the AAI Council, eight of the most prestigious members, elected to their positions by the membership. The AAI is professionally managed by a hired staff with diverse expertise including scientists who are AAI members.

Each year, AAI gives approximately 500 grants and awards to talented early- and mid-career scientists to cultivate the next generation of leaders and investigators, and AAI recognizes the most senior and accomplished members with a variety of career awards. Through the annual meeting,The Journal of Immunology, courses, and the work of its many committees, AAI continues to push forward the boundaries of knowledge in the field and improve the quality of professional life for its members. AAI provides a strong central voice for immunologists, bringing members’ science and issues to the attention of policymakers, funding agencies, and the public.

Not even Synnott could possibly have imagined what that first meeting on a hot summer day in Minneapolis would bring.

References

- Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

- Clapesattle, Helen. Dr. Webb of Colorado Springs. Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press, 1984.

- Coca, Arthur F. “AFC History beginning of Journal of Immunology.” undated [c. 1951]. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.Colebrook, Leonard. Almroth Wright: Provocative Doctor and Thinker. London: William Heineman, 1954.

- Colebrook, Leonard. “Almroth Edward Wright. 1861-1947.” Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 6, no. 17 (1948): 297–314.

- Cope, Zachary. Almroth Wright: Founder of Modern Vaccine-therapy. London: Nelson, 1966.

- Crosby, Alfred W. America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Dunnill, Michael S. The Plato of Praed Street: The Life And Times of Almroth Wright. London: Royal Society of Medicine, 2001.

- Gay, Frederick P. “Immunology: A Medical Science Developed through Animal Experimentation.” Journal of the American Medical Association 56, no. 8 (1911): 578–583.

- Hektoen, Ludvig. “Opsonins and Other Antibodies.” Science 29, no. 737 (1909): 241–248.

- Kolmer, John A., Martin H. Synnott, and A. Parker Hitchens. “Resolutions upon the Death of Dr. Richard Weil.” 30 March 1918. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Pettit, Dorothy A. and Janice Bailie. A Cruel Wind: Pandemic Flu in America, 1918–1920. Murfreesboro, TN: Timberlane Books, 2008.

- Synnott, Martin. “A Historical Sketch,” 1914. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Talmage, David W. “Presidential Address: Beyond Cellular Immunology.” The Journal of Immunology 123, no. 1 (1979): 1–5.

- Wright, Almroth E. Studies on Immunisation and Their Application to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Bacterial Infections. London: Archibald Constable & Co., 1909.

- “Immunology,” Oxford English Dictionary, http://www.oed.com (accessed March 19, 2012).

- Letter from Arthur F. Coca to Geoffrey Edsall. August 30, 1915. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Letter from David J. Kalinski to “Members of the Society for Serology and Hematology.” c. 1920. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Letter from Willard J. Stone to John A. Kolmer. December 24, 1917. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD

- “Major R. Weil Dies at Camp Wheeler.” New York Times. 20 November 1917.

- “Major Richard Weil, M.O.R.C.” The Journal of Immunology 3, no. 1 (1918): IN1-vii.

- “Medical News.” Journal of the American Medical Association 61, no. 23 (1913): 2079.

- Minutes of the First Annual Meeting of the American Association of Immunologists. June 22, 1914. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Minutes of the Meeting of the Council of the American Association of Immunologists. March 31, 1920. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.

- Roll of Charter Members. c. 1914. AAI Archive, Rockville, MD.