The Geography of Immunology

How Honolulu’s Chinatown "Went Up in Smoke"

by Charles Richter and John S. Emrich

July 2020, pages 30–35

IMMUNOLOGY2020™ was to have featured a history exhibit exploring the interplay between immunology and public health in Hawai‘i, including a retrospective on the 1899–1900 bubonic plague quarantine in Honolulu. Following the unfortunate cancellation of the AAI annual meeting due to public health restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the History Office of AAI is pleased to present the following, expanded version of the exhibit for members and other readers of the AAI Newsletter.

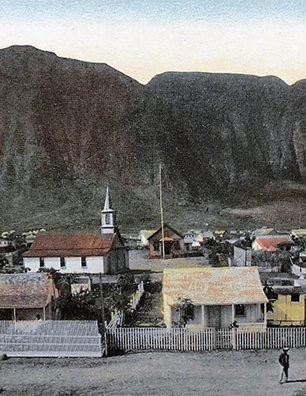

Kaumakapili Church after the fire, 1900

Kaumakapili Church after the fire, 1900

Hawai'i State ArchivesBubonic plague (Yersinia pestis), responsible for the worst pandemics in history, was unknown in Hawai‘i until the last days of the 19th century. When it appeared there, local government health authorities reacted swiftly and severely. The resulting quarantines and public health measures turned into a local disaster and a tragedy for Honolulu’s large Chinese population.

The Third Plague Pandemic

When a plague outbreak began in China in 1860, triggering the world's third plague pandemic, experience from previous outbreaks in other parts of the world demonstrated that the disease was more than a substantial health threat; it was one that conveyed terror of historic proportion. Death from the disease was inevitably painful and gruesome, and depending on the virulence of the strain, fatality rates could range from 35% to 90%. The populations previously struck by pandemic bubonic plague had experienced mortality rates so high that it was difficult to count the total deaths.

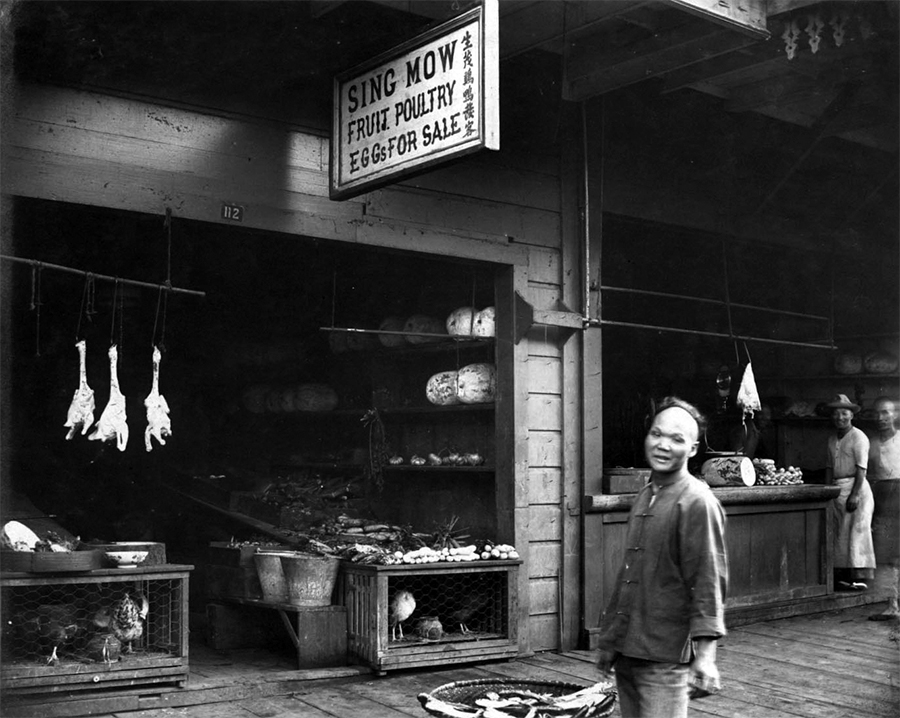

Chinatown before the fire

Chinatown before the fire

Hawai'i State ArchivesThe Plague of Justinian (biovar Antiqua) occurred from 500 to 700 CE, peaking in 541–542, and resulted in 25–100 million deaths. The Black Death (biovar Medievalis), which occurred during the 14th century, peaked between 1347–1351 in Europe and resulted in 75–200 million deaths in Asia, North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.

As news of the emerging outbreak in China began to spread, public health officials around the world became alarmed, particularly those in Asia and the Pacific Islands. By the mid-1890s, the third plague pandemic was well underway, traveling via overland and shipping trade routes to countries around the globe, including Hong Kong, India, Egypt, Japan, South Africa, France, Great Britain, and Australia.

This pandemic, however, provided researchers the ability to study the plague at the microscopic level for the first time. In 1894, bacteriologists Shibasaburo Kitasato and Alexandre Yersin traveled to Hong Kong to study the plague outbreaks in Asia and—independently of one another—managed that year to identify the bacillus responsible for the disease. A year later, Paul-Louis Simond, a Pasteur researcher in Bombay, India, demonstrated that fleas were the vector that transmitted the plague bacterium.

Precautions in Hawai‘i

The growing threat of plague outbreaks led the Hawaiian government (see sidebar pg. 34) to intensify inspections of all ships in Chinese and Japanese ports bound for Hawai‘i. Sand Island in Honolulu Harbor became “Quarantine Island,” where all ships from ports where outbreaks had occurred were held for a week. Initially, the measures proved effective: although plague spread throughout other Pacific islands, Hawai‘i remained apparently safe.

Unknown to nearly everyone in Honolulu, however, plague quietly arrived in the city’s harbor in June 1899 on the Japanese passenger liner Nippon Maru bound for San Francisco. The first signs had been detected at the ship’s first stop in Nagasaki, where a teenage passenger died on May 26. He had no outward signs of disease, but Japanese medical officers made a diagnosis of bubonic plague by visual examination of his glands under a microscope. The Nippon Maru was then held in a week-long quarantine, during which the ship was washed with carbolic acid and all its contents steamed. Only after the decontamination was it allowed to continue its voyage to Honolulu.

Another passenger died on the approach to Hawai‘i, and upon the vessel’s arrival, the Hawaiian government’s bacteriologist found “considerable numbers of a short bacillus, rounded at both ends, and like the bacillus of bubonic plague.” No cargo was allowed off the ship, mainland-bound passengers were not permitted to disembark, and the few Honolulu-bound passengers were transferred to a separate quarantine ship. However, no efforts were made to prevent rats from escaping the quarantined ship. Health authorities in Honolulu decided not to make this case public.

Chinatown, Honolulu

Cordon sanitaire of Chinatown, c. Dec. 1899 – Jan. 1900

Cordon sanitaire of Chinatown, c. Dec. 1899 – Jan. 1900

Hawai'i State ArchivesChinese visitations to Hawai‘i date to the late 18th century, when Chinese sailors arrived in the islands along with the earliest European and American explorers and traders. The first permanent residents came in 1823 and, by 1840, 10% of the 400 foreigners living in Honolulu were Chinese. The rise of the sugar industry in the 1850s brought a new wave of Chinese laborers seeking work on the plantations. Most did not work the sugar fields for long; they found work on smaller farms or went into business for themselves. By 1884, 18,254 Chinese residents made up 22.7% of Hawai‘i’s population and represented the largest non-Hawaiian ethnic group in the islands.

Most Chinese in Honolulu lived and worked in the city’s Chinatown, a 14-block neighborhood bordered by Honolulu Harbor to the west, Nu‘uanu Stream to the north, and downtown Honolulu to the south. It was a densely populated district, home to approximately 7,000 people and many Chinese- and Japanese-owned businesses by the turn of the century.

Plague and Quarantine in Honolulu

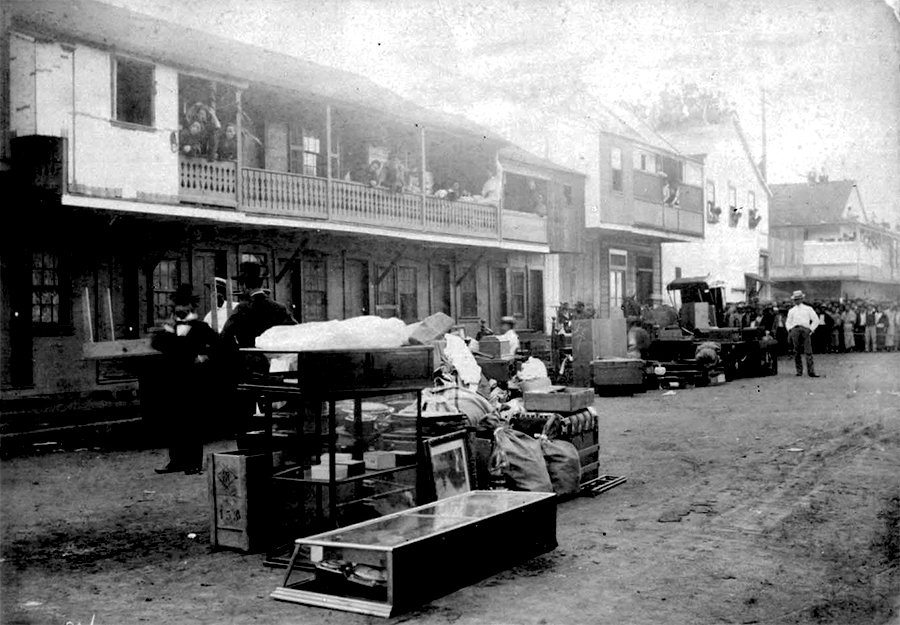

The first case of the flea-borne disease emerged when You Chong, a bookkeeper in Honolulu’s Chinatown, fell ill on December 9, 1899, and developed telltale buboes before dying three days later. Four neighbors succumbed quickly thereafter. By that time, plague had likely been spreading quietly among the local rat population for months. Unfortunately, although the bacillus had been identified five years earlier, still very little was understood about how it behaved. Belongings in the street, c. Dec. 1899 – Jan. 1900

Belongings in the street, c. Dec. 1899 – Jan. 1900

Hawai'i State Archives

On December 13, Honolulu newspapers announced the threat of plague and asked for volunteers to report to the Territorial Board of Health (BoH) to begin inspections of properties. Two days later, they confirmed that several people had indeed died from plague. The BoH closed interisland ship traffic, sealed off Chinatown, and restricted travel in and out of Honolulu. A corps of volunteers began inspections to find any additional cases. Believing that plague germs could live inside walls, under floors, and amongst personal belongings, they sprayed premises with various disinfectant solutions, including sulfuric and carbolic acids. When no further cases were found for a week, the quarantine was lifted on December 19.

A Second Wave and Quarantine

The week of Christmas, however, brought at least four new cases of plague. The BoH blamed the residents of Chinatown for the outbreak, reflecting long-held racist stereotypes about their standards of cleanliness or the foods they ate. The board also distributed a multi-lingual pamphlet promoting cleanliness and citing Kitasato’s research on plague. By 3:00 AM on December 28, National Guard troops enforced a cordon sanitaire—a literal rope barrier in the streets—to prevent 10,000 people from leaving the 14-block Chinatown neighborhood. News of the situation was slow to arrive to the mainland: on December 30, while the new quarantine was in effect, stateside newspapers proclaimed that “bubonic plague has been stamped out in Honolulu.”

Sanitary Fires

Fighting the fire in Chinatown, Jan. 1900

Fighting the fire in Chinatown, Jan. 1900

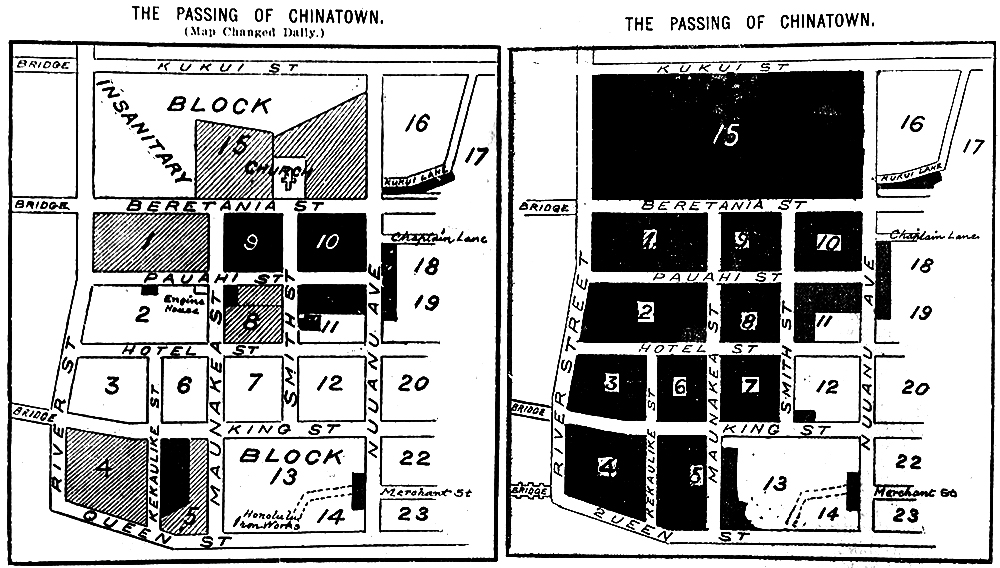

Hawai'i State ArchivesThe situation took an ever darker turn when the BoH, frustrated by the pace of abatement and hoping to reopen Honolulu more quickly, began setting fire to homes and businesses where plague was found. For the first three weeks of January, buildings were destroyed by “sanitary fires” every day. Readers of the Honolulu Advertiser could track the intentional demolition of Chinatown through maps updated daily to show which blocks had been burned or marked for burning.

Inferno

This tactic turned disastrous on January 20 when strong winds blew flying embers from one of the fires onto the wooden steeples of the recently constructed Kaumakapili Church. As if a spark had landed in a tinderbox, the gothic church quickly burned to the ground and flames spread to neighboring buildings. The out-of-control Chinatown inferno generated heat so intense it melted metal cookware, but the citizen guards wielding axe handles insisted on maintaining the quarantine line until the fire forced everyone to flee. The blaze destroyed 60 acres of Chinatown and the surrounding neighborhoods, leaving more than 4,000 people homeless and only five gutted buildings standing.

Even after the fire was extinguished, the BoH continued to set controlled burns in the emptied district, fortunately with no further conflagrations. With the horrific failure of the quarantine measures, authorities placed the former residents of Chinatown into detention camps to minimize the spread of the disease. Cases nevertheless continued to appear for the next two months, including on the big island of Hawai‘i. Ultimately, the BoH reported that the Honolulu plague outbreak produced a total of 71 diagnosed cases and 61 deaths through March 31, 1900.

“The Passing of Chinatown” before (January 20) and after (January 24) the fire, Honolulu Advertiser, 1900

“The Passing of Chinatown” before (January 20) and after (January 24) the fire, Honolulu Advertiser, 1900

Hawai'i State Archives

Plague Reaches the United States

Just after midnight on March 6, 1900, bubonic plague arrived in the continental United States. In San Francisco, the dead body of Chick Gin, a 41-year-old Chinese laborer, was discovered in the basement of the Globe Hotel, a rundown boarding house in Chinatown. This discovery set in motion public health measures, including quarantines; cordon sanitaire; intensive disinfecting efforts that included burning personal property; and racist stereotypes that were similar, if not more pronounced, than those that recently ended in Honolulu. It also led to the establishment of a federal plague laboratory in 1903, which would become home to a number of future AAI members and their research over the next few decades.

George McCoy and Anti-plague Efforts in Hawai‘i

In October 1911, George W. McCoy (AAI 1915, president 1922–23) arrived in Hawai‘i to lead the Leprosy Investigation Station, but he also brought with him years of experience with plague.

Shortly after the 1899–1900 Honolulu plague outbreak, McCoy had been sent to the Philippines to serve as a quarantine officer on his first assignment with the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS). In the Philippine Commission’s annual report to the PHS, McCoy described his frustration with the ineffective policies employed against diseases such as cholera. He was later assigned to postings in China and Japan, where he served as one of the inspectors checking ships bound for Hawai‘i for indications of plague, and then to the Plague Laboratory in San Francisco, which he led from 1908 until his posting to Honolulu in 1911.

Plague had continued to show up occasionally in the rural areas of the Hawaiian Islands, so McCoy instigated a survey of cases both prior to his arrival and during his tenure there. His findings showed that the disease was not limited to any ethnic group; the victims were ethnically and economically diverse. Large-scale rodent reduction efforts resulted in the capture and extermination of tens of thousands of rats and mice. From 1910 to 1913, one in every 1,442 rodents examined was found to be infected with plague.

A New Concept in Plague Transmission

By the 1930s, the concept developed by Karl F. Meyer (AAI 1922, president 1940–41) of a rodent population acting as a reservoir of disease had yielded more effective plague abatement techniques, which were employed in Hawai‘i by the PHS and BoH to successfully reduce rat populations and, consequently, potential human exposure to plague.

See also “A Chronological Overview of Hawai‘i and Public Health” that was inset in the published version of this article

References

- Barde, Robert. “Prelude to the Plague: Public Health and Politics at America’s Pacific Gateway, 1899.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 58, no. 2.

- Bibel, David J. and T. H. Chen. “Diagnosis of Plague: an Analysis of the Yersin Kitasato Controversy.” Bacteriological Review 40, no. 3.

- Dopmeyer, A. L. “Plague Eradicative Measures on the Island of Maui, Territory of Hawaii.” Public Health Reports 51, no. 45.

- Markel, Howard. When Germs Travel: Six Major Epidemics That Have Invaded America and the Fears They Have Unleashed. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.

- McCoy, George W. “Plague in Hawaii: With Special Reference to Its Occurrence on the Northern Coast of the Island of Hawaii.” Public Health Reports 29, no. 25.

- Michael, Jerrold M. “The 1899–1900 Plague Epidemic in Hawaii, USA.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 26, no. 1.

- Mohr, James C. Plague and Fire: Battling Black Death and the 1900 Burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Nordyke, Eleanor C. and Richard K. C. Lee. “The Chinese in Hawai‘i: A Historical and Demographic Perspective.” Hawaiian Journal of History 23.

- Richter, Charles and John S. Emrich. “Karl F. Meyer: The Renaissance Immunologist.” AAI Newsletter, June/July 2018.

- Tansey, Tilli. “Plague in San Francisco: rats, racism and reform.” Nature 568, no. 7753.

- “Bubonic Plague Has Been Stamped Out in Honolulu.” San Francisco Examiner. 30 December 1899.

- “Chinatown Historic District (Honolulu).” U.S. National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/places/chinatownhistoric-district-honolulu.htm (last updated August 16, 2019).

- “Fifth Annual Report of the Philippine Commission. 1904, Part 2.” Washington: Government Printing Office, 1905.

- “History of Kaumakapili Church.” Kaumakapili Church, http://www.kaumakapili.org/about-us/history.html (accessed May 5, 2020).

- “McCoy, George W.” Office of History, National Institutes of Health, https://onih.pastperfectonline.com/byperson?keyword=McCoy%2C+George+W (accessed May 5, 2020).