The Geography of Immunology

A Brief History of Immunology in Portland

by Charles Richter and John S. Emrich

March 2022

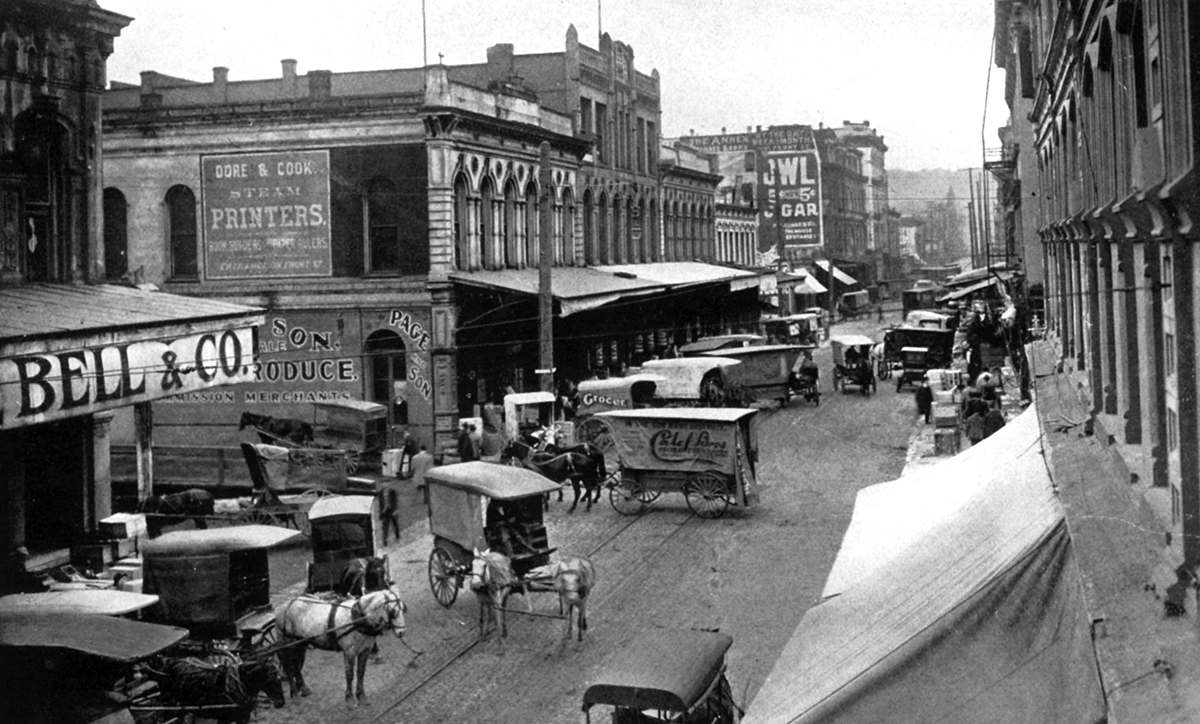

When AAI was founded in 1913, the city of Portland, Oregon, was experiencing rapid growth—the population had doubled in the previous 10 years, making it the fifth largest city in the West behind San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Denver. Founded 16 years before the outbreak of the American Civil War, its growth was owed to its strategic proximity at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers to the agricultural Tualatin Valley and easy access to the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River.

For hundreds of years prior to European exploration and settlement of the area, the location proved beneficial for the native communities. It served as the site of villages of the Multnomah, Kathlamet, Clackamas, bands of Chinook, Tualatin Kalapuya, Molalla and other tribes and bands of native peoples. By the mid-19th century, most Native Americans in Oregon were forced onto reservations. Following the forced relocation, a series of federal laws, notably the General Allotment Act of 1887 (referred to as the Dawes Act), were designed to permanently remove and/or assimilate Native people.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Portland was endeavoring to shake its reputation as a filthy, dangerous town that still possessed a significant amount of Old West miner character. It hosted the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition; three of the bridges across the Willamette River that connected the city and gave it the nickname of “Bridgetown” had been built; and visitors could take a two-and-a-half-hour trolley tour around all the latest, most modern sights.

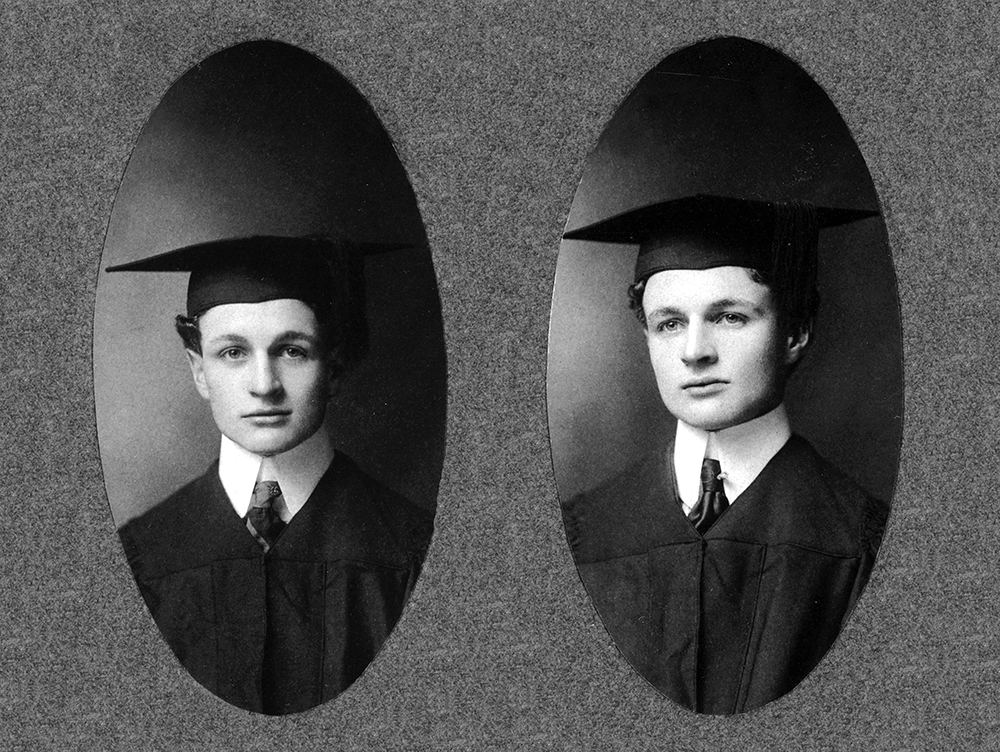

The Matson Twins

Ralph (L) and Ray (R) Matson, 1902

Ralph (L) and Ray (R) Matson, 1902

OHSU Digital Collections In this booming port city, one physician scientist joined AAI as a charter member. Ralph C. Matson (AAI 1913) and his twin brother, Ray W. Matson, were born in Brookville, Pennsylvania, in 1880 and moved as children to Oregon. The twins lived parallel lives, both graduating from the University of Oregon Department of Medicine in 1902 and interning at Portland’s Good Samaritan Hospital until 1905. They both did postgraduate studies at various European hospitals and universities, as was common at the time. At St. Mary’s Hospital in London, Ralph worked under Almroth Wright (AAI 1914) and alongside Alexander Fleming (AAI 1914) in the bacteriology laboratory.

In 1909, the Matson brothers began positions at the first tuberculosis facility in the Pacific Northwest, the Portland Open Air Sanatorium. Ralph served as a bacteriologist, and Ray worked as a pathologist. Within three years, the twins were made co-directors of the sanatorium, just as the state was pushing to make all tuberculosis sanatoria public. They advised the state on a comprehensive public health plan to fight the “white plague” with a combination of public and private institutions. The brothers were liberal in their use of x-ray technology before the dangers of radiation were fully known; one surgeon could only tell the twins apart by the distinctive patterns of x-ray scars on their hands.

Ralph Matson was a logical candidate to be a charter member of AAI: he was a pioneer in the clinical treatment of tuberculosis, which was in its infancy. Other tuberculosis researchers among the charter group included the first president of AAI, Gerald B. Webb (AAI 1913, president 1913–15), and Karl von Ruck (AAI 1913).

Ralph Matson prepping for surgery

Ralph Matson prepping for surgery

OHSU Digital CollectionsLike other early AAI members, including future AAI president Stanhope Bayne-Jones (AAI 1917, president 1930–31), Matson went to France in 1916 to join the British Expeditionary Forces (BEF) prior to American involvement in the First World War. He was reunited with Wright, now the consulting physician for the BEF, who requested his service at the research laboratory established at Boulogne-sur-Mer, France.

After the war, the Matson brothers returned to the sanatorium. Ralph lectured to crowds of thousands about his experience in the war. He became one of the greatest thoracic surgeons of his era and remained active both in private practice and as a teacher at the University of Oregon Medical School until his death in 1945. Ray died in a spectacular manner in 1934 when his sports car, driven by fur coat model Jeanne Ingalls, crashed into a concrete barricade on Portland’s Burnside bridge at 2:30 a.m.

Growth of Portland Biomedical Research

Univ. of Oregon Medical School, c. 1940–48

Univ. of Oregon Medical School, c. 1940–48

OHSU Digital CollectionsSince the earliest days of the city, biomedical research in Portland has centered on the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). Established in 1887 as the University of Oregon (UO) Medical Department, it was the first medical school in the Pacific Northwest. A merger with the medical education program of Willamette University formed the University of Oregon Medical School, and in 1974 it became an independent institution.

After Matson, there were no AAI members in Portland until Arthur W. Frisch (AAI 1956), who joined the faculty of UO Medical School as professor of bacteriology in 1946 from Wayne State University. He became chair of the Department of Bacteriology in 1956 and served in that capacity until 1972. Frisch’s main research interests were serotyping and the legal aspects of blood groups. He was known as an immunologist to his coworkers in the bacteriology department.

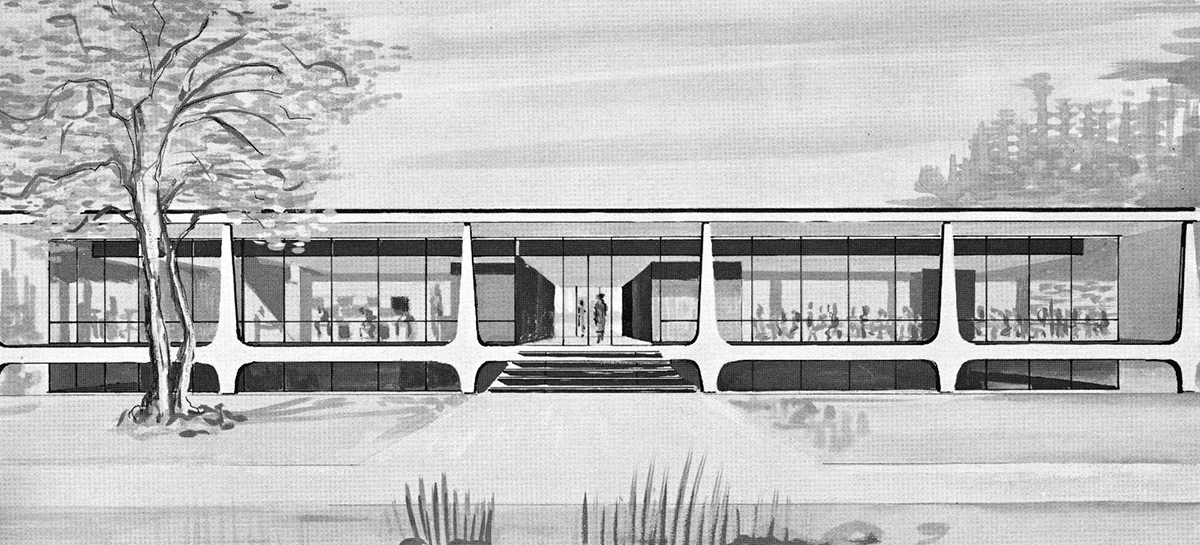

In 1962, with a $1.9 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, the Oregon National Primate Research Center began operations outside Portland with the OU Medical School as its host institution. There, the hundreds of monkeys, apes, and other primate specimens were used in a wide range of research in four major areas: reproductive biology, cardiovascular and metabolic disease, cutaneous biology, and immune diseases. Arthur Malley (AAI 1969) joined the staff in 1964 and conducted research in immunology and biochemistry until his retirement in 1995. In addition to his research at the primate center, Malley taught immunology at Reed College for a number of years.

Rendering of Central Services Building, ONPRC

Rendering of Central Services Building, ONPRC

OHSU Digital Collections

The Oregon state legislature changed the name of the UO Medical School to Oregon Health Sciences University in 1981. By that time, AAI members were represented there in several specialties, including pathology, ophthalmology, and dermatology, in addition to the Department of Microbiology and Immunology. In 2001, the university merged with the Oregon Graduate Institute and the new institution was named the Oregon Health & Science University.

Independent Research in Immunotherapy

Of the many independent research institutions in the Portland area, the one that has had the largest AAI representation is the Earl A. Chiles Research Institute, today part of the Providence Cancer Institute in Portland. Established in 1987 for general medical research, it became primarily focused on cancer research in 1993 when Walter J. Urba (AAI 1988) was recruited from the National Cancer Institute to become its director—a position he still holds today.

By 1996, an early human trial of a breast cancer immunotherapy using an alleogenic cell line and CD80 was conducted by Urba and Deric Schoof (AAI 1990).

Front Avenue, Portland, 1910

Front Avenue, Portland, 1910

Portland City ArchivesWhile no vaccine was developed from that trial, the study did show immunizing effects that would inform later studies. The Chiles Research Institute continues to conduct important basic research and develop promising cancer immunotherapies.

IMMUNOLOGY2022™ in Portland

At the 105th annual meeting in Portland, you will have the opportunity to learn much more about the history of immunology in Oregon and the surrounding region. We hope you will visit the AAI History Exhibit to learn more about the significant contributions made to the field by AAI members living in the West!

References

- Anderson, Karen S. “Tumor Vaccines for Breast Cancer.” Cancer Investigation 27, no 4.

- Curry-Stevens, Ann, Amanda Cross-Hemmer, and Coalition of Communities of Color. The Native American Community in Multnomah County: An Unsettling Profile. Portland, OR: Portland State University.

- Emrich, John S. and Bo Peery. “Industry Representation in Early AAI.” AAI Newsletter, March 2015.

- Emrich, John S. and Bo Peery. “Stanhope Bayne-Jones: One Soldier-Scientist’s Experience during WWI.” AAI Newsletter, December 2012.

- Meyer, Ernest Alan. Interview by Lesley Hallick, 10 February 2010. Oral History Program, Historical Collections & Archives, Oregon Health & Science University.

- Schoof, D. D., et al. “Immunization of metastatic breast cancer patients with CD80-modified breast cancer cells and GM-GSF.” Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 451.

- Tuhy, John E. Annals of the Thoracic Clinic. Portland, OR, Multnomah County Medical Society: 1978.

- “10 corrections measures breeze through House.” Corvallis Gazette-Times. April 30, 1981.

- “$1,917,275 Grant for Study of Rhesus-Monkey Traits.” Louisville Courier-Journal. April 27, 1960.

- “Dr. Ralph C. Matson to Leave for France.” Oregon Daily Journal. May 7, 1916.

- “Dr. Ray W. Matson and Jeanne Ingalls Killed in Auto Crash.” Salem Capital Journal. September 12, 1934.

- “Matson, Ralph Charles (21 January 1880–26 October 1945).” American National Biography Online, www.anb.org/articles/12/12-01512.html (accessed March 1, 2021).

- “Medical News.” Journal of the American Medical Association 161, no. 9: 887.

- “Obituary—Ralph C. Matson, 1880–1945,” American Review of Tuberculosis 53 no. 5.

- “Object to West Plans.” Salem Statesman Journal. October 22, 1912.